#3 - What a Country

For years I had read everything I could get my hands on about what it’s like to be living in America. Pored over all the ads for cars and washing machines and refrigerators in Reader’s Digest and The Saturday Evening Post. Watched From here to Eternity and The High and the Mighty and The Glenn Miller Story a gazillion times until I was sure I knew all I needed to know to hit Main Street, USA running. Even mingled with dependents’ kids at Patch Barracks, a U.S. Army garrison outside of Stuttgart, Germany before coming here. Should have added ‘brush up on philosophy’ to the list:

I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing. Socrates

It soon became clear all the research I had done still wasn’t enough. My integration into the American way of life turned out to be anything but seamless, more like one ‘Aha’ moment after another.

Topping the list were the little things, the comic bits. Like walking into the powder room at the RKO Palace, the fanciest movie theater in Rochester, New York. In Germany, powder rooms were places in castles where medieval combatants stored gun powder. What was gun powder doing in a movie theater one might ask? In hindsight, one should have. Had I known the street interpretation of the phrase ‘I need to powder my nose,’ just connecting the dots would have completed the picture. Instead, curiosity had me open the door and barge in before common sense could sound the alarm. If interrupting a congregation of ladies, dressed to the nines and doing what comes naturally in their private sanctuary wasn’t uncomfortable enough, having to back out into the bright, chandeliered glare of a busy lobby during my hasty retreat nicely finished it.

Then there was the time shortly after my arrival in Rochester when my cousin Bill Vogt showed up at 14 Wooden Street in a new Aquatone Blue and Snowshoe White ’55 Ford and asked whether I wanted to go for a ride, maybe drive down to Seabreeze on Lake Ontario and get a hot dog. I jumped at the chance of a ride but withheld judgment about sampling dog meat. To my relief, the sign behind the counter at Vic and Irv’s told of a choice between ‘beef – red’ and ‘pork – white’, dispelling any reservations. I probably would have eaten this American favorite anyway without first seeing a list of its ingredients, on the grounds that ‘when in Rome, do as the Romans …’ But this made for a much better day all around, just knowing.

As an aside, ‘porkers’ with onions and hot sauce are as much a specialty in Rochester as chicken wings are in Buffalo, our neighbors sixty miles to the west. On your next visit to our friendly city, take a lunch break on Hot Dog Row at Seabreeze and ask for a white hot.

Not every misstep went the distance and came to a red-faced climax in the proverbial china shop. Here is one that didn’t. While on a double date with an Army buddy (U.S. Army Reserve, which I joined in 1957, the year after my arrival), the four of us were cruising down Lakeshore Boulevard along Lake Ontario in my friend’s 1956 sapphire white and gold, D-500 hemi-equipped Dodge Golden Lancer.

This was my first double date in America, and because such a date would have been difficult to pull off in the shadow of the ruins of postwar Germany, and also when you don’t have a car, I'm not shy telling you that this was my first double date, anywhere! I did know, having done some research, that when a guy invites a girl on a double date, not bringing a car to the event is bad etiquette. I also had a pretty good idea that walking up to her front door in the pouring rain with an umbrella would take all the romance out of it. Which is why, until cars became as common a fixture in German households as Levi’s and Coca Cola, double dating a "Fräulein" remained a uniquely American experience.

Somewhere along the way, my friend suggested we should watch the submarine races being held here tonight. Might be fun to take in after the movie, he said. Did I hear that right? Lake Ontario is a big lake and deep enough, but submarine races? In the dark and underwater? I’ll stop here for a minute to let that sink in.

For reasons that seemed to escape no one but me, our dates began to giggle. The first thing that came to my clueless mind was “where would we even park for that?” Oh, c’mon, really? Watching U-boats racing in pitch darkness with two playful young ladies in the car and that’s the part you’re wondering about? It’s one thing to arouse suspicion in a girl that her blind date might be an oaf. It’s another to ask a dopey question and remove all doubt. Luckily, I kept quiet and solved the puzzle on my own. It wasn’t difficult.

KLM Flight 633 had landed in New York on July 7, 1956. It had been a long flight in a propeller-driven Lockheed L-1049C Super Constellation. As the first pressurized airliner in widespread use, the Connie had departed Stuttgart, Germany in late afternoon the day before, arriving in Amsterdam at sundown. After a refueling stop at Shannon, we took off around midnight for the transatlantic leg, touching down at Idlewild (now JFK) around lunchtime. The entire trip had taken the better part of twenty-four hours. Today we complain when the overnight hop between New York and Amsterdam takes more than eight.

The first eye-opener came at daybreak when I looked down from my window seat and noticed we were flying over land. Could it be we had reached America already? An hour passed, then another, then two more – and still no sight of the skyscrapers of Manhattan. Returning to my seat after a break to stretch my legs I heard the pilot announce we were leaving Nova Scotia and would be landing in New York in three hours. Three more hours?! Good Lord, how big is this country?

Years later, while stationed at Fort Hood and sharing the details of my first flight across the Atlantic with a local resident, the quick-witted Texan reckoned with a grin that America must be really big to hold all of Texas. Had he been referring to Europe, he would have been half right. Europe is relatively small, with borders so close that one good hiccup can transport you to another zip code. That wasn’t going to happen that morning on Flight 633. The sheer scale of America felt unbelievably liberating. The memory of it hasn’t gone away. I still feel I’m stepping out of a suit of armor whenever I come back from a trip abroad. Good to be home, New York.

The second surprise struck just minutes after I got off the airplane. Anxious to make my connecting flight to Rochester, I hadn’t paid much attention to the station wagons parked near the roll-away airstairs. The gate was dead ahead less than half the length of a football field. I could see the gate agent waiting and was practically there — so close — when one of the station wagons pulled up behind me and I was asked by the driver to "come aboard." I later learned that it was bad form to walk to the gate. In the 50s, flying was reserved for the rich and famous, and those privileged few were accustomed to being driven. Walking was for people who worked for a living. And with a mere twenty-five dollars in my pocket when our plane touched down in New York, I was undeniably neither rich nor privileged.

In Rohrbronn I had to walk four kilometers — 2.5 miles — to and from the train station in Winterbach just to commute to high school. The idea of keeping a caravan of cars and chauffeurs at the ready to drive the short distance from the gate to the arriving plane, round up all the passengers, then drive back to the gate to drop them off was laughable. We could all have leisurely strolled to the gate in minutes.

What do you mean the 2 km stroll downhill back to Winterbach tonight, on the same unlit cobblestone path, will be the easy part ?!?

The third eye-opener took place in Rochester a few days after my arrival, when my uncle Eugen with whose family I was staying asked whether I wanted to come with him to buy some beer. Of course I did, funny he should ask. This was going to be my new homeland. There would be a million things to see and do while settling in to become an American. It was too early to have compiled a list, but had there been such a list, getting beer would totally have been on it.

When I asked my uncle where we were going to get this beer, he said at the A&P supermarket. Oh well, that’s just around the corner, a two-minute walk. Except, he explained while opening the door to his 1952 Studebaker Champion parked out front, we were taking the car. Oh really! To get beer? In a curious way it made sense because we came home with a case of it, twenty-four bottles, a somewhat larger scale than how beer was typically bought in Germany. Still, the supermarket was literally a stone’s throw away and I could easily have carried a case but decided to bite my tongue and adopt a laissez-faire attitude on American methods of transport – from now on.

Times have changed since the fifties. Today, more people walk or take the stairs because walking is good for the heart and, so we’re told, nearly as beneficial as sex to promote circulation. I do know it’s a perfect excuse to get a dog. Dogs are great. A dog is said to be a man’s best friend and “Honey, I’m taking the dog out for a walk” supremely expedites getting out of the house, no questions asked.

What hasn’t changed is a phenomenon that oddly took a while to sink in. Yes, there were a lot of cars, and people drove them as if gas cost 23¢ a gallon (which it did). And of course Americans were not all little people with tiny heads the way illustrators portrayed them in period ads to make the cars look bigger which, gim’me a break, was the last thing they needed to be. I could process that. But all the car ads in Reader’s Digest and The Saturday Evening Post combined couldn’t have prepared me for the real eye-opener: the near universal requisite of a garage, or at minimum a driveway. Practically every house had one.

This was monumental. No other country on the planet could claim such a broad based, vibrant middle class. I now understood. It wasn’t Carnegie or Rockefeller who the world thought of when people wished they had a rich uncle in America. It was Joe the Plumber.

Compare that to Rohrbronn, the village in Germany where I grew up. When I left, its people population was around three hundred. Its car population was one – two, if you counted Hedwig’s converted tractor. Emil Benzenhőfer owned a black 170 D Mercedes that he used as a taxi in a neighboring town but kept in a garage in the village. Hedwig Sigle, our next door neighbor, had managed to get her hands on a surplus Jeep left over from the war that she used in lieu of a cow. There were no other cars in the village to use in lieu of anything. To be fair, Germany’s postwar recovery at the time was still in its infancy.

You would have found bicycles, though few people used them to commute to work. Bikes aren’t much good for commutes when you live up on a hill. True, you get to coast effortlessly down the hill in the morning when you’re bright-eyed and bushy tailed, but then you have to push the 50-pound bike with fat balloon tires back up the hill in the evening, exhausted from working all day. Besides, nobody was eager to ride a bicycle "gone wild" down a slick icy road in the winter, a reluctance shared with the owners of motorcycles that began to emerge after Germany got back on its feet.

Rosa Waibel, the midwife, did ride a Zündapp 200 motorcycle year ’round, including on snow and ice in the winter, a feat for which she was universally given high marks. Her motoring skills and commitment helped me enter this world on a cold April Tuesday in my mother’s bedroom.

To travel anywhere in the early postwar years beyond the boundary of the village, everyone but the midwife and Emil Benzenhőfer had to walk thirty minutes down the hill to Winterbach, then ride in a noisy and drafty rail car behind a steam-powered locomotive the rest of the way. In my case, that meant twenty minutes on the train each way to high school in Schorndorf, and an hour by train and streetcar to Möhrlin GmbH in Stuttgart-Feuerbach where I completed a three-year sales and marketing apprenticeship.

The entire office staff at Möhrlin saying goodbye on the last day of my apprenticeship. I can't think of a happier work environment and a more cheerful and creative group of people to teach me how to run a business. As you can tell, there's more to the German stereotype than Ump-Pah-Pah and Lederhosen. I have no clue why the end of my tie was supposed to get attached to in secretary's hair in the photo on the left.

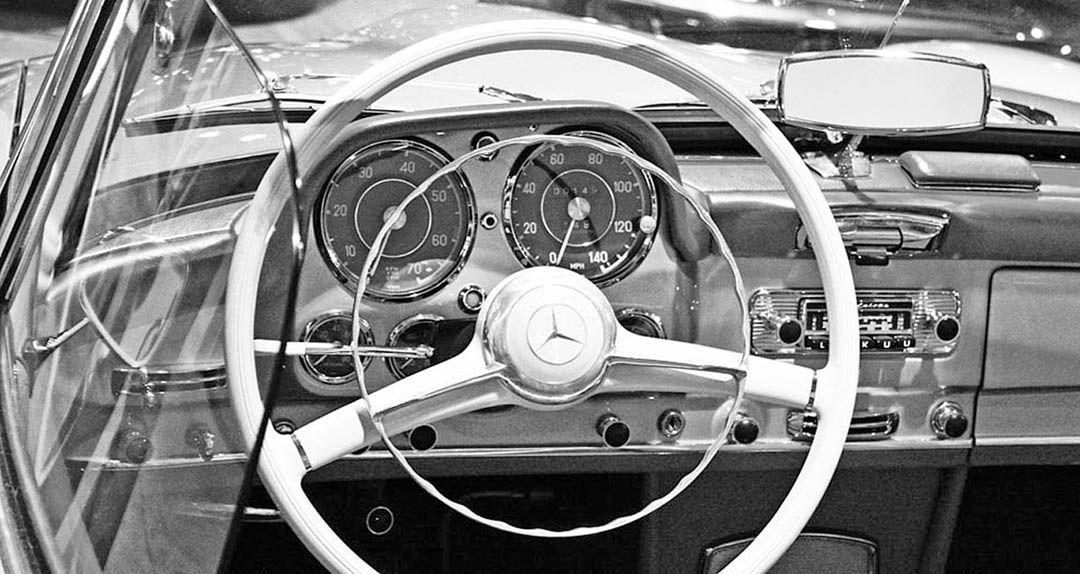

Möhrlin is where I got my first ride in a sports car, a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 190 SL. With 104 horses the car was no speed demon, barely reaching a hundred miles an hour on a level stretch of Autobahn, but boy did it look the part. The company had two Mercedes-Benz cars in their garage: the 190 SL and a black 300 4-door sedan, both driven by the same chauffeur.

There was a reason why Möhrlin GmbH owned two Daimler executive cars driven by one chauffeur: Daimler AG was far and away its best customer, its biggest source of income. When Herr Schmitt, Möhrlin’s CEO, came calling on Daimler to promote goodwill or negotiate a new contract, he had damn well better show up in a Mercedes-Benz. This sort of etiquette may not be practiced everywhere, but it is in Germany. At least it was when I was working there. It may have changed. My brother Eugen told me a few years ago that supermarket signs there no longer say “7 items or else.”

On the flip side, Enzo Ferrari is said to have commuted daily from his home in Modena to his office – in a Fiat 1100! He owned the company, so nobody with an ounce of self-preservation instinct would dare hold him accountable. When a reporter did ask, Enzo replied “What’s so surprising about that? You’re just as likely to see Giovanni Agnelli driving a Ferrari.” Agnelli was the head of Fiat. You gotta love the Italian free spirit.

Doing the research for this first book of the Shelby Cobra Trilogy, I came to realize how little I knew about motoring’s early history. Here I was, born and raised near the birthplace of both the automobile and the internal combustion engine, practically in the backyard of its inventors, and I had seldom taken the time to read up on it. For instance, did you know that the first person ever to take a car for a real drive, to actually go somewhere with it, was a woman?

Funny story. In 1888, without telling her husband or bothering to get permission from the authorities (problematic in its own right – where would she have gone to apply for a permit, and a permit to do what?), Bertha Benz packed her two teenage sons into the experimental vehicle and drove from Mannheim to Pforzheim and back. The car they used was the three-wheeler patented two years earlier by Karl Benz, Bertha’s husband. The world’s first automobile had only seen a few short ’round the block test drives when his wife took it out for the clandestine one hundred and twenty-mile shakedown cruise – to visit her mother.

Way to go, Bertha!

The trip had its moments. Bertha served as her own mechanic and used her garter to repair the ignition while a blacksmith helped mend a chain. When the wooden brakes began to fail she had a cobbler line them with leather, resulting in the world’s first brake pads. The Motorwagen’s two lone gears weren’t enough for climbing hills; to get to the top her two sons often had to push. As soon as she got back to Mannheim, this trailblazing young entrepreneur suggested putting in an extra gear.

Sunday driver my ass!

Fast forward to July 7, 1956. In one overnight dash, by the simple act of crossing the Atlantic Ocean, I had been transported into a modern Land of Oz filled with cars painted in bright candy colors and adorned with miles of shiny chrome. No munchkins and flying monkeys to be seen anywhere. And no itinerant cows unless you sought them out in the countryside. I had stumbled into America’s love affair with the automobile, at a time when Detroit was the center of the universe.ord’s ‘Tin Lizzy’ had evolved to where automobiles were more than just vehicles that allowed people to drive into town and to other states instead of spending their whole life on the farm. The soldiers and sailors had come home. Before long there was a car parked in every driveway.

In the fifties you could watch a movie at a drive-in, pull into a ‘Big Boy’ where a carhop on roller skates would bring you a coke and a cheeseburger with fries on a window tray, even attend a live Sunday sermon given by some forward-thinking pastor over wired-up outdoor speakers – all without leaving your car. You could get married or divorced in your car in Vegas, and order a daiquiri at a drive-through in New Orleans. Laissez les bons temps rouler! the other things you can no longer do. Except, of course, for the drive-through daiquiri that you can still get in New Orleans, in a plastic go-cup sealed with a lid. That, and maybe watch a movie in one of the nostalgia drive-ins that are popping up.

The most meaningful changes have come in what we drive and how we navigate. If someone had handed you the keys to a brand new car in the fifties, only the most adventurous among us would have driven it across the U.S.A. on Route 66. With GPS omnipresent on every cellphone, and driverless cars a reality, the two technologies will soon merge to where it won’t matter that the pinhead in the next lane is texting.

Interstate highways were approved by Congress in 1956, the year I arrived. Two things stand out. It’s easy to become addicted to cars in America, to become a car guy like Jay Leno. And I’ve been an American a really long time, with the sun still shining on the happiest decision of my life.

The comedian Yakov Smirnoff summed it up perfectly: “Then I got to New York. New York is great. I walked out of the airplane and saw my name written, big letters, Smirnoff. America loves Smirnoff. I said to myself "What a Country”."

What a country, indeed!

Copyright 2022 - Helmut Heindel