#4 - Gone Fishing

Ambushed by the prospect of losing my first job in America, I wasn’t sure how to react when two sour-faced officials from the Laborers’ International Union of North America emerged from a freshly car-washed black Lincoln sedan and suggested I put down the hoe and stop doing what I was doing presently which was mixing mud. For those unfamiliar, grey mud and white plaster was how we built houses before sheetrock became popular and replaced it. I’ll get back to that in a minute.

The matter at hand, explained one of the officials, was my perilous lack of membership in the LIUNA. They were here, he said, to encourage me to either become a dues-paying member or get off the job site. He then said, “We’ll wait.” The year was 1956, a time when labor racketeering was rampant and would soon to be investigated by the McLellan Committee. Most American workers already understood that failure to join the brotherhood was never in anyone’s best interest. I, on the other hand, had stepped off the plane onto American soil just a few months earlier and had no clue.

Fair enough. The fellow with the loose tie and sweaty brow asked nicely, no expletives, while at the same time leaving little doubt about the severity of his message. You can do that when you have the build and demeanor of an NFL linebacker. Besides, I hated that job and was by now three months into it. The Laborers’ International Union of North America was doing me a favor.

Lath and plaster was a building process used to finish interior walls and ceilings in Canada and the United States until the late 1950s when drywall began to replace it. By all accounts, working as a laborer for a plastering company was one of the toughest jobs in the industry. At 148 pounds dripping wet and fresh out of a white-collar office environment I wasn’t built for schlepping heavy loads of gray mud and white plaster up steep layers of scaffolding. My aunt Helene tried all sorts of remedies to keep the contusions on my right shoulder from proliferating. By the end of the first week, we had eliminated gauze and Kotex pads and settled on pot holders attached with safety pins to the underside of my work shirt.

The reason I kept working as a laborer despite the physical rigors was simple. U.S. Immigration laws said you had to be sponsored by an American citizen; and you needed proof you could support yourself once you got here. The owner of the plastering company who hired me was the American citizen who sponsored me. I felt obligated. Quitting after only three months on the job ran counter to how I was brought up. Getting kicked off by the union, fortuitous as that may appear, was clearly unpremeditated and now out of my hands. True, I could have applied for union membership. But even my sponsor said “don’t be stupid” and counseled against it. Strong sentiments from the man most affected. Thank you, Laborers’ International Union of North America. You pulled me out from under a hard rock and into a more suitable line of work without asking for a dime. So nice!

Less than a week after the sudden end of my career in construction I was hired by the Bausch & Lomb Optical Company in Rochester, thanks to a referral from a kind, caring lady who lived two houses down from my uncle and had learned of my predicament. My new job was to handpick component parts for microscopes and binoculars out of wooden bins in the stock room, then deliver those parts to old-world craftsmen who would assemble them into finished products. I had graduated from a $2.00 an hour laborer to a $1.42 an hour stock boy. It was indoor work with health care benefits and no union dues, easily worth the cut in pay. Premiums alone for mandatory union-provided health insurance might have swallowed up the difference. The coverage was supplemental (the union plan only covered exotic contingencies that basic health plans didn’t), so I still needed Blue Cross. Not saying the union policy was a scam. Just because no laborer ever got hit by a flying pig or an errant moon rock doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen – someday.

Compared to my first three months in America, the next few years were heaven. Hardly a day went by when I wasn’t having the time of my life, thankful to be living in America. To top it off, it was all happening during the fabulous fifties, when Mom stayed home and Dad made the daily commute to work, apple-pie idyllic and iconic Americana in the making.

It would be naïve to expect such feel-good existence to be solely the product of an era or a new homeland, even when that homeland is as exceptional as the United States. It’s rooted in the lifestyle and decency of the people around you, in families who welcome you into their house and make you feel at home. And in friends who are goodhearted and fun to be with and who see life through the same lens you do.

You’ve already met my uncle Eugen and aunt Helene and my cousins Peter and Brigitte, their son and daughter. You haven’t met the Vogts. I wish you could have. You would have enjoyed their calm, cheerful, and oh so contagious approach to life. Did I mention their outgoing and fun-loving nature?

Bill Vogt was the patriarch and my uncle and a bus driver for the Rochester Transit Company. One day he was driving his GM bus down Main Street when he caught sight of uncle Eugen walking past Sibley’s Department Store. It was mid-afternoon so there were few pedestrians, enabling uncle Bill to drive the big city bus right up onto the empty sidewalk, trailing Eugen by maybe three feet. Before his friend could sense what was looming behind him, Bill blew the horn. Would surprise me if uncle Eugen stayed around Sibley’s long enough to collect the socks he’d jumped out of.

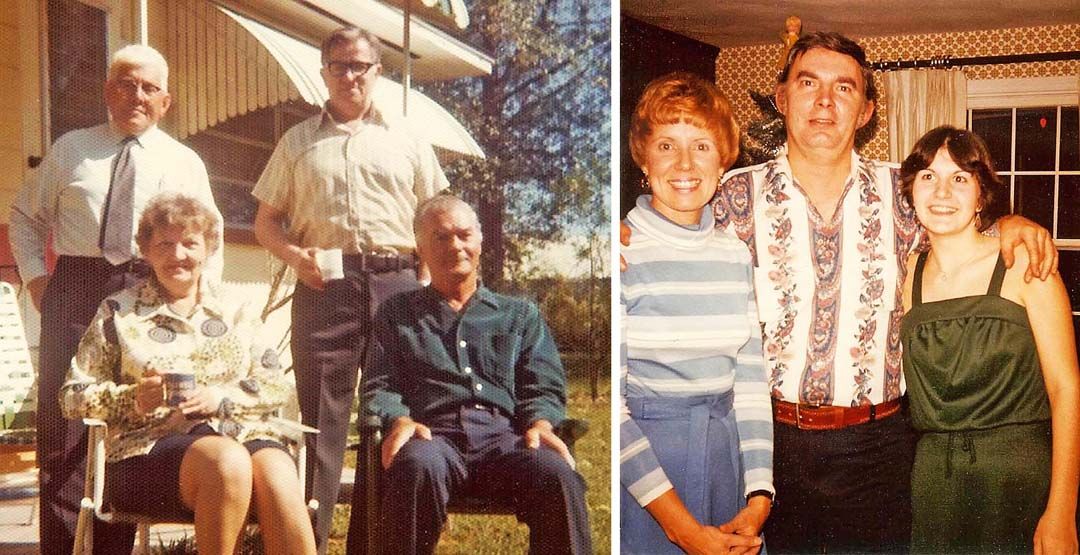

Left to right: Terry's uncle Ernst, my aunt Francis, uncle Eddy, uncle Bill, cousins Renee, Bill, and Beth Ann.

The Vogt’s weren’t rich, not in the conventional sense, but Bill and Francis had saved their pennies over the years to buy a summer cottage on Grenell Island in the St. Lawrence Seaway. They accomplished this while raising four children, Bill, Teena, Bob, and Kenny, a testament to the power of a dream and the discipline and hard work to make it reality. This despite the Great Depression that cost Bill his job as a golf pro and forced him to dye his golf shoes black so he could look for a different line of work

My cousins, left to right: Chuck, Teena, Bob, Kenny, and Bob Vogt.

Grenell is part of an island chain that straddles the border between the United States and Canada, with New York State on one side and the Canadian province of Ontario on the other. Here you’ll find the “Thousand Islands-Frontenac Arch” region, designated a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve in 2002. The 1,864 islands range in size from forty square miles to tiny outcroppings. To be counted in the group, an island must stay above water 365 days a year and support at least one living tree.

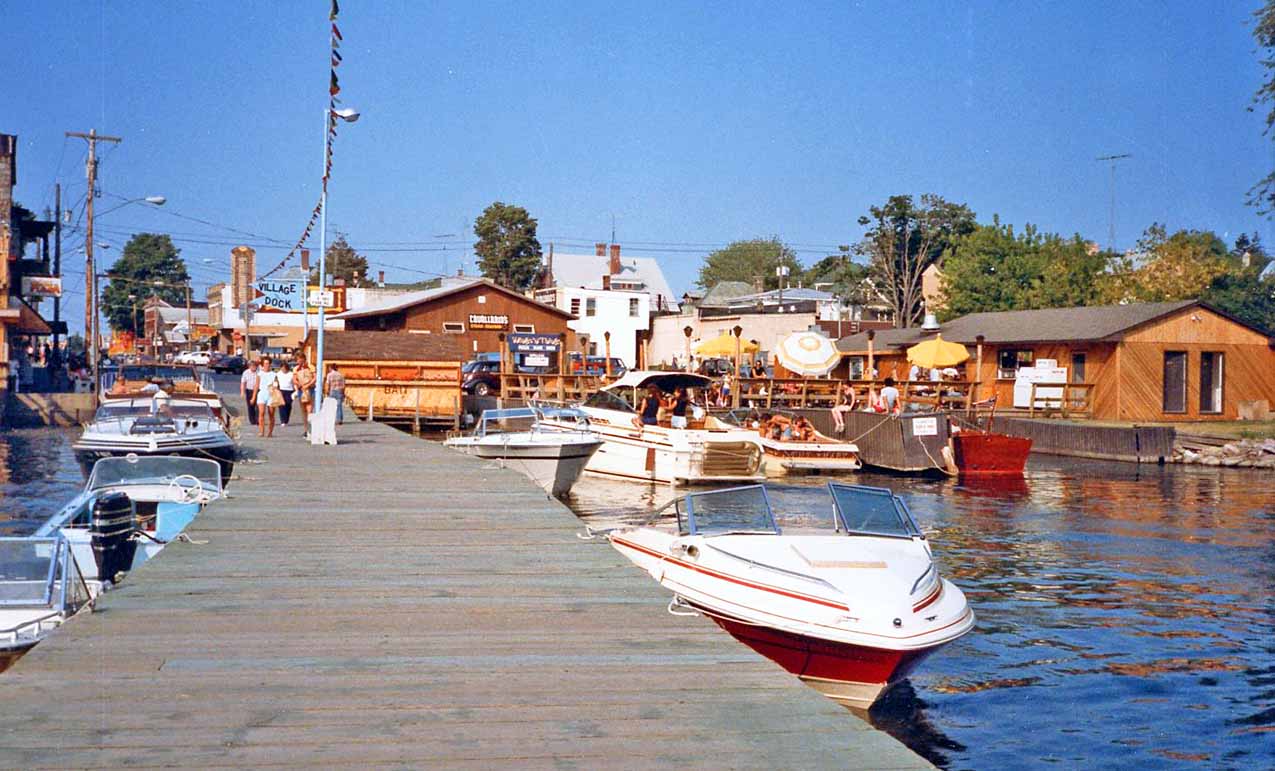

Vacationers have been coming to the Thousand Islands for more than 150 years to enjoy the breathtaking beauty that inspired the Iroquois Indians to name it the ‘Garden of the Great Spirit.’ Waters once patrolled by pirates and bootleggers are now cruised by summer residents and tour boats.

During Prohibition, when alcohol was banned on one-half of the islands but legal on the other half just paddle strokes away, no place in America could offer more ideal working conditions to the rum runners of the day. One creditable story describes how two gamblers regularly invited local revenuers to their scheduled poker nights for which a cottage had been rented specifically. The revenuers were so preoccupied with consistently winning against the exceptionally inept card players that the heavy river traffic on poker nights went unnoticed.

The region was thrust into the limelight in 1872 when George Pullman of sleeping car fame invited President Ulysses S. Grant to his Thousand Island retreat. Grant asked whether he could bring along two of his celebrated Civil War generals, William Sherman and Philip Sheridan. This became a major news event at precisely the same time that the National Association of Newspaper Editors held their annual convention in the region. The rapid growth that followed became known as the “Rush of ‘72.”

Traveling by private rail cars from New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago, millionaire industrialists began to put the Thousand Islands on the map. They came to fish and host lavish parties, but mostly to leave behind the bustling big city life. Several grand hotels provided luxurious accommodations while steamboats offered tours among the islands. There were so many people of power and prestige here during the summer that the New York Times kept a correspondent in the area to report on their activities. Some of the castles the wealthy built on their private islands remain as international landmarks.

Photo right: My Cousin Brigitte and I boarding Chalk's "That's Her" water taxi at Fishers Landing in 1956.

Those are the facts in a nutshell. The reality is more colorful, both in history and natural beauty, but this isn’t the book for it. I doubt I could ever write such a book. My attachment to the region is much too strong to do it justice. What I will tell you is that I found my first love in America on Grenell, one of the nearly two-thousand islands in the St. Lawrence River, a romance made indelible by the splendor of the river and the company of treasured friends, framed by the melancholy of a road not traveled.

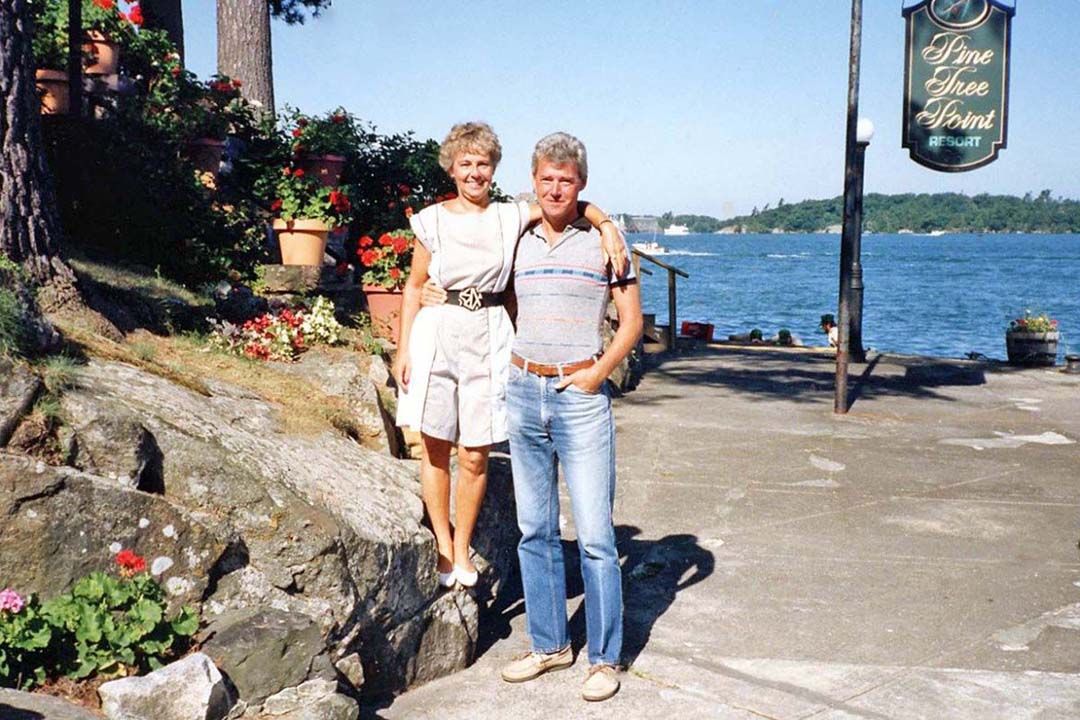

It was a simpler time then, and some of the people who enriched that time have passed on. Unforgettable people like aunt Francis and uncle Bill, and my cousins Teena and Bill and Bob and Kenny. But the memories remain. The pure magic of the place hasn’t gone away. Terry and I try to spend at least one weekend there every summer.

People who own a summer cottage on one of the islands like to tell you that they’re living "on the River." When you live on the River with a boathouse and a boat you’re apparently expected to go fishing. Judging by the signs in the windows of many small stores during the fifties, half of those shops, when closed, let it be known their owners had "Gone Fishin".

It was still pitch black outside when uncle Bill woke me up out of a deep sleep on the living room couch in their cottage. He had turned on the reading lamp on the table next to the couch and was trying to hand me a shot glass full of Seagram’s 7 whiskey. An eye-opener, he called it. Why he thought I needed an eye-opener in the middle of the night became clear when he said we were going fishing. Uncle Bill and I and uncle Eddie.

Eddie drove a delivery truck for the Genesee Brewing Company in Rochester. He had a habit of calling his colorful Polish friends “dumb Pollacks” when an impasse was reached due to clash of opinions. Also for other reasons Eddie said were relevant. There was some flexibility vis-à-vis the country of origin. Being Polish helped but wasn’t mandatory. Eddie would conveniently include male cohorts of lesser roots, save for the parish priest, when unforeseen events cried out for it. Having to fold with a crappy poker hand at the traditional Friday Night Fish Fry at Lynam’s Grill comes to mind. For a time, Lynam’s was owned by members of the Vogt family, cousins Bill and Renee, and Kenny and Alyce.

That Eddie was himself of Polish descent – generally in good humor with an infectious upbeat look at life – ruled out ill intent. Eddie’s friends accepted the Pollack label for what it was, a term of endearment. It was good to be liked by uncle Eddie.

This was my second weekend at the cottage. Based on how much fun everybody said they were having going after bass and perch and stuff, I had spent part of that week’s paycheck on a fishing license and a small rod with a tackle box and assorted lures at Kresge’s Department Store in the Bull’s Head Shopping Center. That may have been premature. I had no idea fish were up at this hour.

On the other hand, the day I arrived I had thrown out a line from the boathouse dock to check out my new fishing gear. It was well past dusk and just as dark then and I didn’t have the lure in the water more than a minute when I felt a tug and hauled in a sunfish. Could be different fish keep different hours.

I didn’t catch a single fish that entire next day. Uncle Bill blamed it on having used my shiny new lures for bait instead of a worm. Voicing agreement, I didn’t have the heart to tell him I never intended to use a worm that day, or any other day. Part of the bargain of leaving behind the small rural village in Germany was the dismissal of compost and foul-smelling dirt and whatever was crawling around in it. So the worm thing wasn’t happening. That, I devoutly believe, is why God invented lures. Recall that I caught my first fish with a lure. It was catch-and-release owing to lack of size, but a fish is a fish.

The rest of the day Bill and Eddie hauled in a fair amount of perch, and I got to listen to their fish stories. Like the time they caught this huge muskie that was so pissed off after they reeled him in that they decided to let him have the boat for a while. I suspect there wasn’t much deliberation. Muskellunge can get up to six feet in length and weigh close to seventy pounds. The locals will argue that “you don’t fish for muskies, you hunt them.” Had I been with Bill and Eddie that day you’d have seen me jump in the river long before the big fish was of a mind to get angry. Size of the boat irrespective.

I debated whether I should tell you about the time I almost burned down uncle Bill’s boathouse. Write what you know about, the experts say, and when you write a book in which every other page deals with the internal combustion engine, you should know enough about internal combustion engines to not burn down a friggin’ boathouse. If you don’t, it makes you look bad.

There was this antique Evinrude outboard, mounted like a fishing trophy on a wall inside the boathouse. It was old and weathered and looked like it hadn’t seen the transom of a boat since the Indian Wars.

“Why aren’t you using this?” I asked.

“It won’t run,” uncle Bill said, “hasn’t in years.”

“Mind if I try?”

“It’s not going to run, don’t waste your time.”

Then I heard him say, walking away: “If it starts, I’ll buy you a beer.” With the outboard still up on the wall at a good working height, the cowling was off in less than five minutes. On first impression, the 2-stroke motor didn’t look much different than the 2-stroke Maico motorcycle motor I had worked on in Germany. Some fresh gas and a few hours of elbow grease later, I had the old antique running. Not well mind you, not in the beginning, but the longer it ran the more encouraging it sounded.

Five minutes into it, all hell broke loose! Out of the exhaust came a shower of sparks spectacular enough to light up the Fourth of July, and in such volume that it filled the boathouse.

Turns out there is a difference between a Maico motor and an Evinrude. The Maico is air-cooled and powers motorcycles. The Evinrude is water-cooled and powers boats. Instructions say to have the Evinrude guzzling water hanging partially submerged off the stern of a watercraft, not sucking air hanging from a wall in a boathouse. Evidently, I didn’t know that.

Oh well, no harm done. The old boathouse on Grenell Island is still standing. I had managed to decarbonize the outboard which for all I know may still be hanging on the wall. And Uncle Bill did buy me that beer, with a shot of Seagram’s 7 whiskey for a chaser, a Boilermaker, he called it.

Copyright 2022 - Helmut Heindel