#2 - Leaving Rohrbronn

Most people will remember their first car, often bought with paper route or tobacco money. Mine was a white BMW 328 Roadster. Magnificent set of wheels, with functional steering and transmission and an overall length of five and a half inches. It was 1/28th the size and a mere fraction of the price of the 153-inch long full-size version that would have let me go on Sunday drives with my girlfriend.

That last point was immaterial because at age fifteen I could no more afford a girlfriend than a real car. Offered a choice between the two I would – in a heartbeat – have opted for the car. Make that any vehicle not equipped with a windup spring motor. A Vespa on life support would have done it.

Two years after buying the toy roadster I was watching a soccer game in a cleared out section of the woods above our village. After the game, two of my classmates and I stumbled on a life-size BMW parked among the pine trees, a just released R51/3 motorcycle. It was the biggest, most badass motorcycle you could buy in Germany in 1951. The sight of two cylinders jutting out horizontally from the boxer motor alone was enough to get your juices flowing.

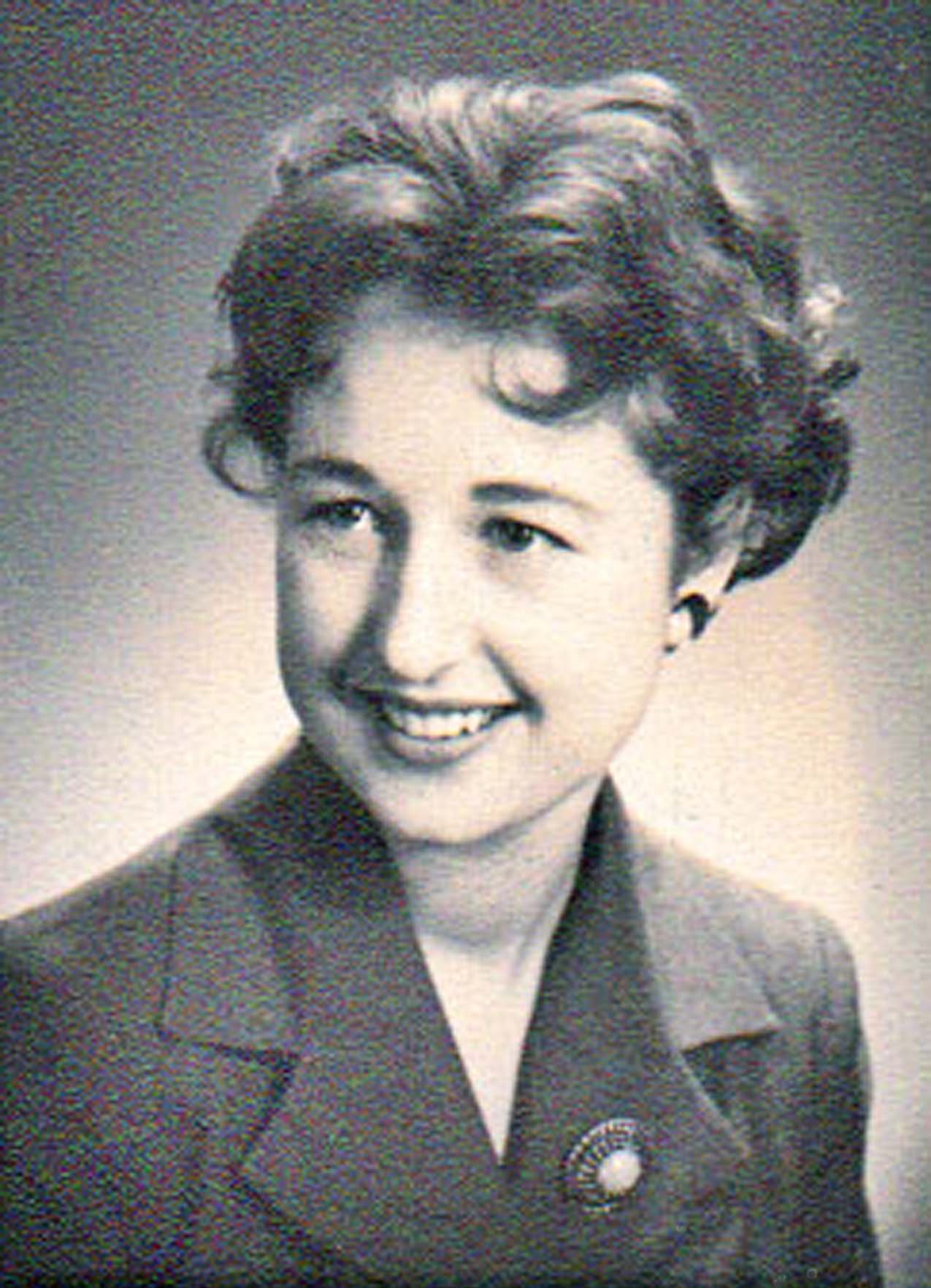

The three of us had barely begun to admire the bike when the owner showed up. Time has erased whatever image of him I might have had in my memory. I can easily remember his girlfriend, a stunningly beautiful young woman. Her trim figure was accentuated by a simple, stylish outfit suggesting mystery but revealing no secrets. Raven black hair and just a touch of makeup on creamy white skin made clear this was no farm girl laboring under a hot sun all day.

Social life can be unsettling when you’re young and male and saddled with the hormones of a fifteen-year old. As this otherworldly creature climbed up on the passenger seat I couldn’t help noticing that she had recently shaved her legs. Not unheard of in the cities of postwar Germany, but uncommon for village folk. And despite the obvious difference in our ages, oddly intriguing.

Just as I was completing a mental picture of how intensely pleasurable life must be when you have the means to attract such a beautiful woman who wears makeup and lipstick and shaves her legs, the owner reached down and fired up the bike by pushing down on the BMW’s kick starter – with his bare hand!

Oh crap! So that’s what it takes. It was never the expensive motorcycle, though I imagine getting to ride on the back of that gorgeous R51/3 could have tipped the scale. No, if I wanted to someday share my life with the girl of my dreams I’d have to work hard to become good something – something big. Lots of endeavors in this world don’t require the ability to hand start a motorcycle. This was excellent news and a relief because the hand starting thing wasn’t happening. The mere specter of it had the bike kicking back and me doing a Nadia Comaneci over the handlebars.

Also not happening in the real world was a fifteen-year-old teenager buying a car or a motorcycle, which I would have been too young to drive in any event. But there was something I could do, and soon enough did: secretly attend motorcycle driver’s school and pass the test, wait for the day I turned sixteen, and at just the right moment over coffee and marble cake which our mother always baked for my birthday, ask for her approval to get my motorcycle license. Her signature was necessary because I was not yet eighteen.

I wasn’t proud to have gone behind her back like that but there were extenuating circumstances – like, what choice did I have? My dad had gone on to the big Oktoberfest in the sky in a motorcycle accident years ago. Dollars to doughnuts my mother would disapprove of seeing me follow in his footsteps. I did get her consent after I promised to never ride a bike in the rain or at night or on the speed-limit-free Autobahn.

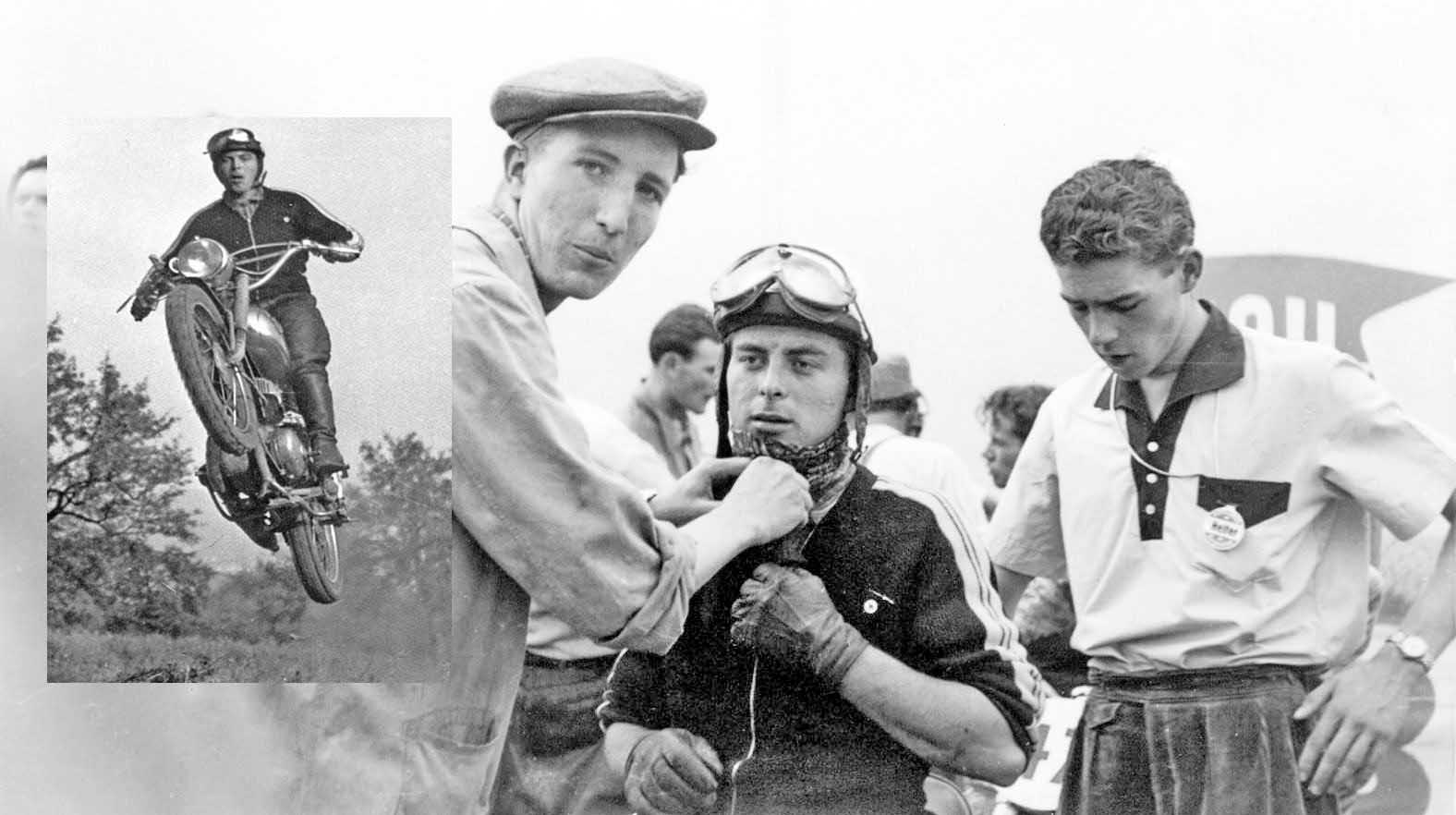

You may be wondering why I thought I needed a motorcycle license when I didn’t own a motorcycle. Part of the answer, I’ll admit, was bragging rights. But the main reason was that Fritz Waibel, a cousin and schoolmate one year my senior, was beginning to move up in the standings while motocrossing his 175 cc 2-stroke Maico.

He asked whether I would consider helping him race it. It would mean working on the bike without wages and traveling to interesting places now and then. I wasn’t crazy about 2-strokes but they were all the rage and you can see where such an opportunity was impossible to say no to when all I needed to say yes was a motorcycle license.

Mom and Dad got married in a church in Winterbach. They couldn't get married in a church in Rohrbronn because there was no church in Rohrbronn. The Lutheran Pastor from the church in Winterbach made house calls as needed, weather permitting. Curiously, the Rohrbronn villagers found they needed to build a church after I had emigrated to America.

Tobacco Money? Oh that! Here I’ll have to take you back a few years to set the stage. Wouldn’t want you to judge as peculiar my fascination with American cars in general, those powered by Ford in particular, and why I thought a showroom stock Shelby Cobra needed more power for a run to the post office. I must have had my reasons. Some of which now escape me and — except for why I’m drawn to Ford products — may best be left unremembered.

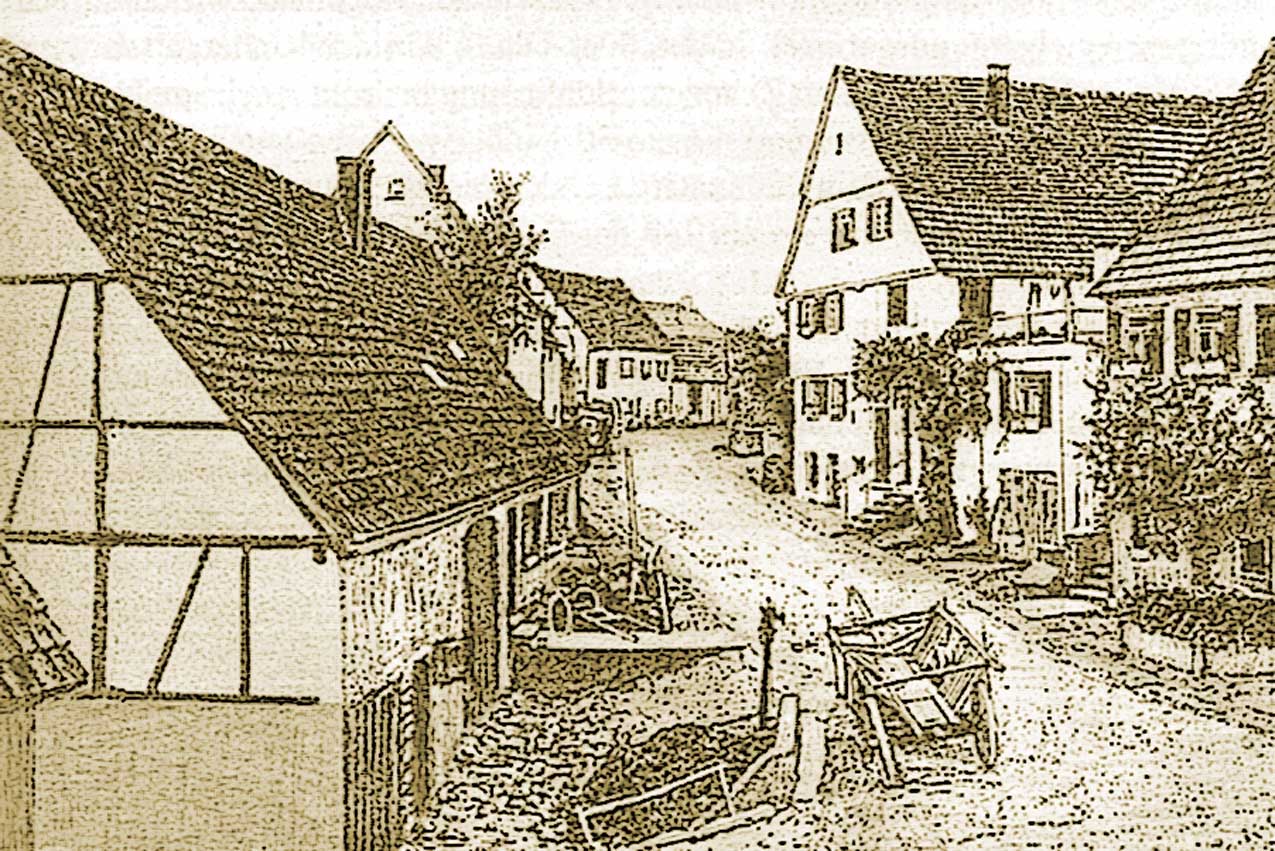

Rohrbronn, up on the hill (aka "Schneckabuckl"), with the outskirts of Winterbach in the foreground. Photographed in the fifties.

I was born in my mother's bedroom in Rohrbronn, a small country village in Germany with a population of around 300, twelve miles east of Stuttgart. My father died in a motorcycle accident when I was a year old while my mother was carrying my sister Erna. Hitler’s ambitions for a "Third Reich" were beginning to escalate into World War II when my Mom became a bride again and bore three more children, my sister Erika and my brothers Eugen and Werner. Sadly, her second husband was killed on the Russian Front when a bomb hit the locomotive he was driving.

Having found the institution of marriage disappointingly short on longevity, she decided she would stay single. Not a decision made on a whim. It meant having to raise five young children in the aftermath of a brutal war, with no partner to support her.

On the left: Our mother with my sister Erna. Taken in September of 1938, a year before Hitler invaded Poland, and Britain and France declared war on Germany, beginning World War II.

On the right: My grandmother (Rosine Vogt) helping me get saddled up for a photo op and pony ride to nowhere.

Compared to children growing up in big cities during the war, village kids were better off. True, we never saw an orange or a banana or anything resembling a Hershey bar, but most village folk had a small vegetable garden and one or two fruit trees and bushes with berries. That’s not to say life in the country was a picnic and that we never went to bed hungry. We did go to bed hungry at times, though not nearly as routinely as most city kids did, and often for reasons young children will tell you aren’t very nice. Take the “check is in the mail” episode my sister Erika shared with me for this chapter.

Throughout the war years, and the years following, our mother knitted socks and children’s clothing to supplement her meager pension, on an ancient knitting machine that had been passed on to her from our grandmother. One particular day a village resident ordered a pair of socks, and the order couldn’t have come at a better time: Save for a few pennies, our mother’s wallet was empty.

Hand-operated and dating back to the early 1920s, the old knitting machine was clearly no speed demon, but by evening, the socks were ready and Erika was designated to deliver them to the woman living just a few houses down the street. The understanding, as always, was cash on delivery. Hurray!!!, we would have bread from the bakery tonight, with marmalade from our cellar. We could have had bread, that is, had the woman not sent my sister back empty-handed, with the message “Tell your mother I’ll pay her when I see her next week.”

Bread, butter, meat, sugar, and other staples were all rationed no matter where you lived. Apples and berries and even potatoes grown in your garden lack protein and only take you so far. But you can make butter at home by letting fresh milk stand overnight and skim off the thin layer of cream the next morning. If you managed to skim off at least half a pint, pour it into a Mason jar and shake vigorously. If you shake the jar for, say, half an hour, you’ll be rewarded with a little yellow clump the size of a golf ball. Your arms will get tired but you keep shaking because when you roast potatoes without first adding butter, they will burn and smell bad and taste horrible.

The biggest advantage of living in a small village was the greatly reduced risk of getting killed by a bomb. Village residents mainly had to keep an eye out for low-flying planes to avoid getting strafed by some trigger-happy cowboy in a P-51 Mustang. The idea was to spot the idiot first so you could take cover behind a house or a large tree.

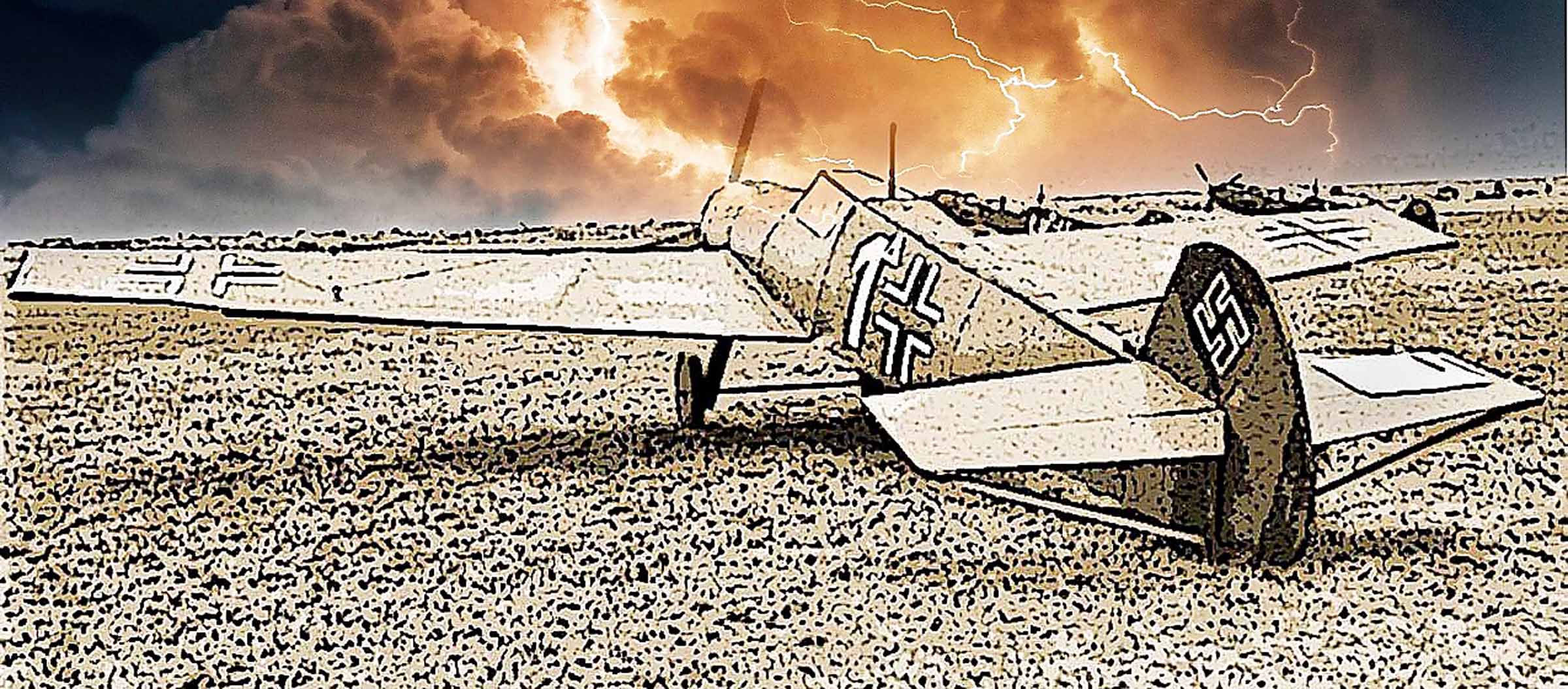

Towards the end of the war, the German air force began to divert some of those risks by hiding easily-recognized German fighter planes in plain sight on an airfield in the valley at the foot of our “Schneckabuckl.” The airfield was as fake as the wooden Bf 109 Messerschmitts parked there. Since we had an unobstructed view of the field from the hill on which we lived, the occasional bombardment of the plywood bait by Allied planes was great theater, free of entrance fees, and consistently celebrated as the highlight of our day.

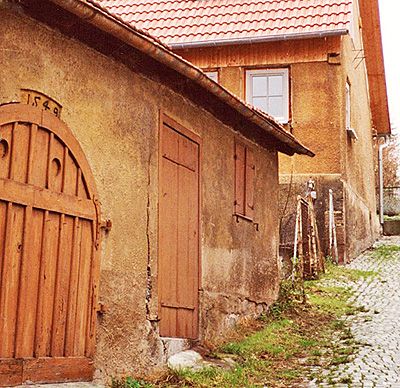

In Rohrbronn none of us "Kriegskinder" (War Children) ever had to make a run for it. My biggest concern was getting trapped indoors while an aerial dogfight was underway overhead and that I might miss it. Being within earshot and line of sight of our house was no safer because it enabled my mother to call me inside and I’d still miss it. Seriously, ma’, like the 400-year old house we lived in would have protected us from airplane parts raining down on us! I swear she had a better sense of when swarms of Allied bombers were going to overfly our village than the guy in charge of the air raid siren.

In our mother’s defense, I have to admit that even empty 50-caliber ammo belts can cause a ton of hurt if you get hit by one, and we found a lot of those after every dogfight, with the most sought-after containing the occasional live round. Here, being inside the house would definitely have offered protection. Understand that my classmates and I were between seven and nine years old at the time. None of us owned toys made in a factory, so mostly what we did was invent games. The gunpowder we managed to extract from live 50-caliber rounds using a rock and a hammer made any game more interesting, heightened the adventure. If you’re unfamiliar with gunpowder, it will explode only when confined. Outside the cartridge, it flash-burns. One of us, uninitiated, had to endure weeks of ridicule until his eyebrows grew back.

Now that I think of it, my mother’s early warning radar may have been one reason I missed some of the dogfights between American B-17s on a bombing mission and German fighter pilots hell-bent on protecting the people living below the American navigator's bombsight. I generally blame it on having to sit through the boredom of a one-room serving six grades schoolhouse in the morning, then having to pick blueberries in the dense Rohrbronn forest in the afternoon to supplement our family income.

In the end, none of that mattered. Regardless of locale, I wouldn't have been able to see or hear any of it because aerial combat between fighter planes and bombers generally took place at altitudes between 25,000 and 30,000 feet.

Though there was this one fateful day when a dogfight ended up being so close that even some adults ventured out to watch. That day was Friday, February 25, 1944. With the temperature in the low sixties, a small family of farmers happened to be working in a field above the village, getting it ready for the spring seeding. Take cover? And give up front-row seats for an aerial battle this close to the action? Not on your life! Besides, where would they have found shelter in the open field? The grownups in the group were leaning on their hoes, mesmerized by the sound and fury playing out over Hößlinswart, a neighboring village separated from Rohrbronn by a small stretch of woods.

When I stepped out onto the street to see what the commotion was about, Mr. Sigle, our neighbor who owned the restaurant and bakery across the alley, was already on his way to where the farmers were standing. Close behind were kids my age. They might have joined Mr. Sigle because we all knew adventures such as this benefitted greatly from having an adult in the group. Then again, they could have flocked to Mr. Sigle because he was seen carrying binoculars.

Once I caught up with the group, I was greeted by the unexpectedly loud noise of exploding cannon shells, a sound I had never heard before. Two German fighters were pursuing a B-17 bomber that had already taken too many hits to maintain enough altitude to make it home across the English Channel. As the B-17 began to drop out of formation, seven white parachutes became visible against a deep blue sky. We waited for more, but that wasn't to be. Minutes later, the huge plane rolled over onto its side and disappeared from view behind the treeline, taking three crew members with it.

And then there was nothing. No clapping of hands, no jubilation. Only an eerie, discomforting silence. Even the noise from the cannons had stopped. By focusing on the airmen jumping from the stricken bomber I had lost track of the German fighters. Chances are they were searching for new targets when it became clear the bomber's condition was terminal.

For the farmers in the field, the show was over. We all had witnessed, just minutes ago, mortal combat in which human beings had lost their lives. But much of the adult population throughout Europe had learned to live with the brutality of war by becoming numb, leaving out the tragic parts, finding peace within themselves only when there was nothing left but the inculpability of numbers. How many hundreds of lives had been lost in Stuttgart that night, or London, or Dresden?

"There's work to do, it'll be dark soon, we have to finish our chores".

If a storyteller thinks enough of storytelling to regard it as a calling, unlike a historian he cannot turn from the sufferings of his characters. A storyteller, unlike a historian, must follow compassion wherever it leads him. -- Norman MacLean, Young Men and Fire

For us "Kriegskinder" living in the backcountry out of harm's way, the air war did little more than intensify our hunt for treasures falling from the sky. Such as the 50-caliber live rounds, priceless on our junior-grade version of a flea market. The same couldn't be said for the bulletproof chunks of glass from B-17 canopies, worthless because the glass clearly wasn't bulletproof. Trading was our way of coping with not having things. When you're still in grammar school, you're not ready to have reduced to numbers the lives of ordinary men, drafted into the military to protect their homeland. At that age, a lack of compassion is reserved for grownups.

But you have to wonder: Are numbers the measure by which all wars are inexorably judged? As a veteran of the Vietnam War who never saw action in Vietnam, I feel nevertheless entitled to point to General Westmoreland's fascination with his daily postings of body counts!

Mr. Sigle and I didn't talk much on the way back. I thanked him for letting me borrow his binoculars, and he asked me whether I still planned to attend the Burg-Gymnasium high school in Schorndorf after the war. The fate of the American flyers didn't come up.

As we learned the next day, the B-17 had crashed below the village of Lehnenberg, four miles northwest of Rohrbronn. Seven of the ten-man crew survived by deploying their parachute. Prior to 1944, allied airmen had only a one in four chance of completing their 25-mission tour.

A few weeks earlier, two German Army officers had come to our front door in full dress uniform. At the time, my stepfather – our mother's second husband – was serving on the Russian front. Our mother instantly knew what the officers had come to tell her. The heartbreak that would so violently invade our home that peaceful evening had already infected untold homes across Europe and North America. It would mercilessly infect thousands more. Before one of the officers could begin to announce "we regret to inform you . . ." our mother had fled through the kitchen into our living room where she collapsed onto the couch, sobbing "no, please, no . . . " She would be crying into her pillow that night for a very long time.

I offered to accept the death certificate on our mother's behalf. The officers agreed, then stayed on a short while to offer their condolences to me and my younger sisters and brother. In her book "The Long Road Home," Martha Raddatz describes the intensity of such a moment in stark language: "That was how these things happened. The doorbell rings and your life changes forever."

Soon, doorbells would be ringing in homes in America, and service members in dress uniforms would announce the death of the three airmen who perished in the crash of the B-17 near Lehnenberg. Three families would be without a son or a husband, and children would wait in vain to jump into the arms of a father who would never again be home for Christmas.

Nothing about war is pretty, but given enough time the mind tends to blot out memories of the raw and the ugly. Acts of kindness will stay with you. I can remember the clip-clop of horseshoes through much of the night as if it happened yesterday. The German Army was retreating on the road behind us, and they needed the horses to pull their trucks which had run out of gas miles ago. Hours passed. With daylight came the rumbling of the tanks of the Americans. We were under parental orders to stay indoors and could only envy classmates who had front row seats because their houses lined the main thoroughfare.

No shots were fired during the clearing of our village, the population of which consisted mainly of women and children and old men at war’s end. Very old men, because any male who could recognize the front end of a rifle and fire it without first taking a nap had already been conscripted into the military.

Some of the conscripts had returned crippled and were now encouraged to join the “Volkssturm” (the peoples’ storm) to defend the fatherland alongside a few seniors similarly predisposed. Not many joined. Even then, their only hostile act consisted of cutting down some pine trees and strategically laying them across the road leading into Rohrbronn, thereby erecting a two-foot-high barrier that may have slowed the advance of the American tanks by all of ten minutes.

Blowing up a bridge would have been a more effective impediment, but thanks to the elevated location of our village there were no creeks or rivers running through it. Hence, no bridges could be blown up in Rohrbronn, which in any event would have tested the expertise of the Volkssturm. Lacking training, getting a few cherry bombs to explode on New Year's Eve might have been a more appropriate assignment.

Quoting from Regiment of the Century, the Story of the 397th U.S. Army Infantry Regiment: "Without encountering any opposition, the First Battalion moved a total distance of six and a half miles to Wüstenrot on April 17, 1945, having cleared Hirrweiler and Bernbach en route. We had gotten used to numerous roadblocks and blown bridges that were intended to slow us down. The ease with which we eliminated these soon struck the enemy as hardly being worth the effort."

By 1943, most able-bodied German men over the age of eighteen had been drafted into the armed forces. Beginning on January 26, 1943, anti-aircraft batteries were manned almost exclusively by conscripted Air Force Service Helpers (commonly called “Flakhelfer”), some as young as fourteen. “Flak” has become both an English and German abbreviation for “Flug Abwehr Kanone” (Anti-aircraft gun). Luckily I dodged the bullet, having celebrated my ninth birthday one month before May 7, 1945, the day World War 2 officially ended in Europe.

In the end, the only thing the Nazi propaganda had accomplished was to terrorize our parents with images of barbaric acts the enemy would subject them to if they let themselves be captured. What was already torturing me and my siblings, on the other hand, was that if we didn’t get out of the house soon the whole show would be over. Watching the American tanks rip up the pavement at the one sharp turn in the village alone would have been good for a week’s worth of conversation. Making us miss that was just wrong.

The American soldiers who came knocking on our front door broke the tension. We had hung a white bed sheet from a window to show we had surrendered, as instructed by flyers dropped from airplanes. Two of the three soldiers checked our house for weapons while the third waited outside. When the inspection was over, they all left calmly, with all the composure imaginable, after having painted a big “OK” on our front door with white chalk.

No raping, no pillaging, no mistreatment of any kind. That's if one overlooks — as any reasonable person should — the pilfering of the bomb sitting in the display cabinet of our rarely used formal dining room. The bomb had landed on the coal tender of my stepfather's locomotive and failed to explode. He apparently thought it would make a nice one-of-a-kind flower vase — a good luck charm, even — when he brought it home on furlough from the Russian front. The same thought is unlikely to have occurred to the American soldier who unexpectedly came face to face with this unique "memento." What on earth was a bomb doing in this family's dining room? For our mother, it became the definitive "Oh My God" moment, and the language barrier wasn't helping any. But her quick wit saved the day. "Helmut, go out and get me some flowers from the flower box. And hurry!"

I can't imagine what the soldier stationed at our front door thought when he saw me charge out, grab some flowers, and dash back inside. But once Mom had finished arranging the flowers in the defused bomb, a picture emerged that really was worth a thousand words. Realizing that the bomb was harmless, and sensing our mothers predicament, the soldier chuckled and, taking a considerable load off Mom's mind, told her "Maax Nix" and confiscated her flower vase.

"Maax Nix" was possibly the first expression American soldiers learned, their way of saying "es macht nichts aus", (it doesn't matter), typical of the laid-back American lifestyle. After discovering the meaning of the chalk marks on our door, the first American idiom we kids added to our vocabulary was far and away "OK".

When our mother's heart had stopped racing, I could see an expression on her face that I can revisit to this day. Never before had I seen such overwhelming relief. The reality must have come flooding in. For the residents of our now cleared village, the war was over. We no longer had to be on constant alert for low-flying planes to avoid getting strafed. Soon, there'd be an end to the nighttime carpet bombings of Stuttgart that had made the sky above that city glow red, while causing the glass in my bedroom window to vibrate from the thunder of the explosions 12 miles away.

We could finally stop sleeping with our clothes on. She had endured and brought her children safely through the misery. “Now can we go out?” I asked. “Yes,” she said, with eyes beginning to get teary from the avalanche of emotions, “but don’t go far and don’t stay out forever. I need to know what’s going on.” With that, she gave us a hug and opened the door. None of us could have imagined the strange world that had risen up during the night and would be waiting for us in the morning. Some of it would melt away within days.

Village Hall and one-room Elementary School in Rohrbronn.

None of us could have imagined the strange world that had risen up during the night and would be waiting for us in the morning. Some of it would melt away within days. Like the Sherman tank parked a few yards from our house with the white star painted on its side and its gun pointed down the only access road into the village. Other less visible elements would irreversibly weave themselves into the German fabric and change that country’s identity and values and way of life forever.

They were already beginning to change mine. Having cautiously stepped around the tank we came onto a scene that couldn’t have been more alien to life amongst the cow stalls and half-timbered “Fachwerk” houses of the village. An African American sergeant sat legs crossed at the edge of a circle of children that had formed around him, passing out candy and oranges and Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum. Any child unfamiliar with chewing gum – meaning all of us – chewed and quickly swallowed it. In the absence of German Language instructions, this was predictable.

For the children and their German parents, the war had ended. The American sergeant would have to fight on. I pray he survived. He must have had children of his own that were waiting for him to come home to America.

Our next encounter with the American Occupiers was too intriguing to walk away from. Happening a stone’s throw away from our house, it was bound to erase any lingering doubts the villagers may have had about the end of hostilities: We heard the unmistakable sound of laughter! One of the soldiers had climbed off the tank and was now engaged in a schmoozefest with our neighbor who lived with her family in the house directly across the cobblestone alley from where the tank was flexing its considerable muscle.

Rosa Schurr had spent several years in America until the outbreak of the war had blindsided her on a visit to Germany. Separated by nothing more than a chainlink fence and no language barrier to contend with (she spoke fluent English), Rosa and the American soldier were exchanging pleasantries. “Frau Schurr, you need to go back into your house,” I kept wanting to tell her. “There’s still fighting going on all around us!” But I kept quiet, afraid that if I caused a scene it might not end well. I was nine years old. The soldier and Rosa kept chatting over the fence for a long time.

On our way back to share with our mother these extraordinary sightings, the enormity of the moment began to rise through the fog of war. My sisters and my brother and I had stumbled onto a landscape we had never come across before. Until today, everything we had learned and experienced — the totality of our world view — was framed by a world war. We were all too young to define by name what we had seen that fateful morning. Days later, after the dust had settled, it became clear: The place we had walked into was Peace.

If only I could have mailed a photo of these eye-opening events to Dr. Goebbels, Hitler’s mouthpiece. No such kindness and generosity by the enemy was portrayed on any of his propaganda posters! Neither was the decency and compassion of the American commander who kept his tanks a humane distance from the retreating Germans. They could easily have wiped out the outgunned and spent convoy. Had they closed the gap, the German troops would have resisted, causing casualties on both sides, but with tanks against horses, the carnage on the German side would have been far greater.

I wish I could tell you that the first few years after the war brought much relief. The hardest hit, as they were during the war, were again the large cities. In Stuttgart more than half of all buildings lay in ruins. The bombings had stopped by April 19, 1945, eighteen days before Germany officially surrendered in Reims, France, but people were still dying from disease and malnutrition. By the spring of 1946 the official ration in the American zone was at most 1,275 calories per day, with some areas receiving as little as 700. In other zones the rations were even lower. The calorie count in a Big Mac cheeseburger – the burger, not the meal – is 530. When there wasn’t enough food to eat in families with children, you could count on the parents to be the last ones to the table. Our family was no exception.

American GIs, glad to be going home to America to reunite with their families.

The chaos was made worse by armed and violent gangs of "Displaced Persons" that terrorized the population and made it dangerous for women to leave the house even in broad daylight. There weren’t enough American MP’s (Military Police) to protect them, and when the newly formed German police were given responsibility for it, they weren’t allowed to carry firearms until late in 1945. The unarmed policemen themselves were often victims of vengeful mob attacks. No one could protect isolated farms. If a farmer got caught hiding a weapon he risked being executed as a partisan by the Allies.

Having developed more than a casual interest in all things American, I was crushed to learn that General Eisenhower, the Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, had been issued a non-fraternization policy that would make it illegal for American soldiers to interact with German residents. I was getting ready to attend Gymnasium (high school) the following year and had planned to learn English for the express purpose of what JCS Policy Directive 1067 now prohibited explicitly. Luckily, Eisenhower softened the orders laid down by the Joint Chiefs of Staff by relaxing the ban in stages to where American soldiers could talk with German children by June of 1945. In September, the prohibition was dropped altogether — to the considerable relief of a contingent of pioneering American soldiers who had been fraternizing with their German girlfriends all along.

Not dropped and continuing in force was one of the more onerous provisions of JCS 1067: No international relief packages could be sent into Germany. The directive had been brewed up in the spring of 1945 by the infamous “Morgenthau Boys.” Universally derided by the in-country military occupation command, the plan exposed not only Germany but much of war-torn Europe to communist ideology and the risk of Russian annexation. Strategic considerations aside, all but the most vengeful could see that the Washington elite was once again out of step with Main Street USA. When the restrictions on parcel post deliveries into Germany were lifted in June of 1946, more than a year after the war had ended, 95,000 relief parcels arrived from the United States in the first shipment.

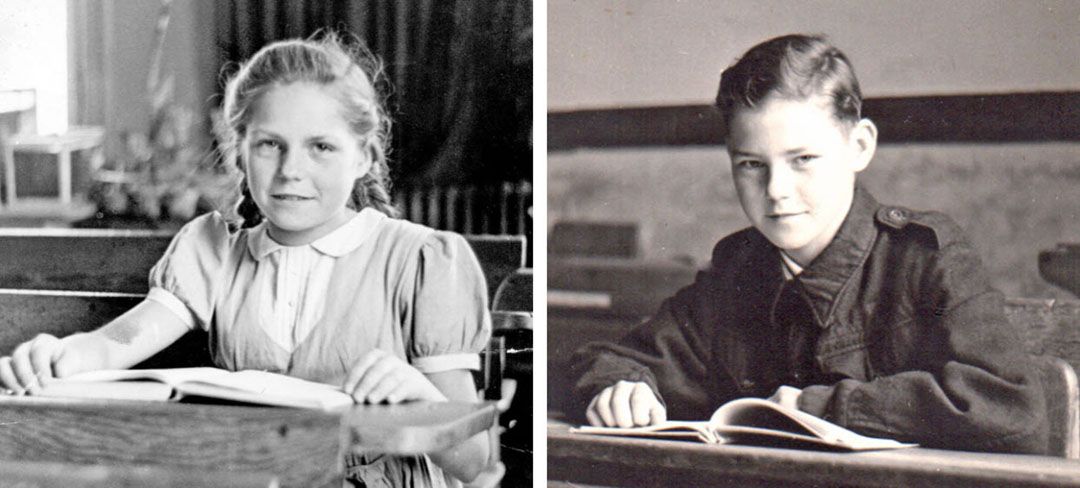

My sister Erna and I studying English in Schorndorf

As if our garden wasn’t enough to make us feel guilty for the starving city kids, we now began to receive CARE packages from two of the dearest and most caring women we had never even heard of: Emma Mooney and Emma Cervini. It turned out they were distant relatives living in Rochester, in upstate New York. Only people who suffered through the hardships and shortages of a war and then received CARE packages from America can fully appreciate how much the generosity and compassion of the two Emmas meant to us. It was Christmas all over whenever the postman delivered one of their packages.

Thank you Emma Cervini, and thank you Emma Mooney, for the cocoa and flour and fine-smelling LUX soap and Crisco and Spam and Nescafé. Also for the black Eisenhower jacket that was only a little oversize but fit well enough to wear to school all winter. It was warm and a nice fashion statement, having come all the way from America. And, oh yeah, those great toys and delicious Hershey bars. Thank you as well for the egg-shaped leather ball, although we had a hard time playing soccer with it.

The currency and tax reforms of June 1948 formally kickstarted Germany’s rapid economic recovery, Ludwig Erhard’s ‘Wirtschaftswunder’, and life began to improve in earnest. As did my English. I was now able to read Life Magazine and The Saturday Evening Post (when I could afford to buy them). At some point I discovered the free ‘America House’ library where I was introduced to Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck, along with ‘Life in these United States’ and excerpts from other writers in the pages of Reader’s Digest.

With each passing year, the gulf between the dreary, antiquated village life and the glamour and excitement streaming at me from the advertising pages in American magazines became wider. What was it like living in Rohrbronn, our village up on the hill? No running hot water, no sewers, no central heat, no flushing toilets. One payphone, a bakery, and a general store. If you felt the need to attend church on Sunday you had to walk half an hour to Winterbach, a neighboring village. Local news was brought to you by the town crier who walked the length of the village, stopping at the same houses every evening to ring his bell and read, from a sheet of paper, the day’s announcements he himself had written.

Main Thoroughfare in old Rohrbronn, 1945 - 1955

Our mother at the ancient wood stove on which she used to cook the evening meal throughout the war years and well into the sixties.

Only a certified back-to-the-earth lunatic would describe as quaint or romantic the straw-lined cow stalls taking up most of the ground floor of a 1940’s Swabian farmhouse, not to mention the dung heap conveniently located in front of it.

Not every house boarded cows, just most of them. Strangely, what bothered me the most wasn’t the aroma – cow dung mixed with straw doesn’t actually smell that bad once you get used to it. No, it was the darkness, the dim incandescent lights that greeted you when you entered a barn late in the evening to buy produce from a farmer. Just a smattering of fixtures, and no bulb brighter than 15 watts, even years after the war had ended.

Also, I don’t like dirt, generally. Freshly organically enriched dirt (think cow manure) in particular. That and the boring, backbreaking fieldwork kind of soured me on nature. So, yeah, to this day.

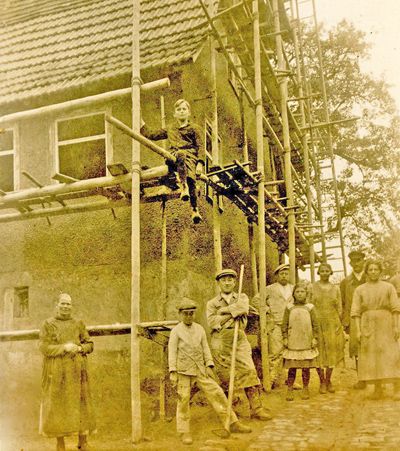

That's the Schurr house in the foreground, with our house uphill from it. Both were built in 1549, just beyond the Late Medieval Period that ended in 1500. They are recorded to be the first two houses built in the village. Note the construction date over the entrance to the cellar of the Schurr house. The photo on the right was likely taken in the mid to late 1800s when the exterior of our house needed repair.

Luckily, we were too poor to own cows, which left us raising rabbits and chickens. We did have a radio, and when I was home alone, it was tuned to AFN, the American Forces Network. We also had something else, something every child should be given in abundance: The undying love and affection of a mother. On a return visit to the old house we all grew up in, my girlfriend Terry sensed the remnants of that devotion when she said “There’s a lot of love in these walls.” Thankfully, despite the hard times and shortages, love was one basic necessity we were never without.

By the summer of 1948, the German currency was in shambles and near useless as a means of payment. Goods were scarce, food was rationed, and going shopping meant trading watches and jewelry and cameras on the black market for food and coal for the winter. We even bartered with the American soldiers, almost from the beginning: Schnapps distilled by local farmers from hard apple cider in exchange for gasoline. Gallon for a gallon. I always thought the Americans were on the sweet end of that deal!

I said I would explain tobacco money. Until the currency reform in June of 1948, cigarettes were the unofficial means of payment in postwar Germany for pretty much anything. Because Lucky Strikes, Chesterfields, and Camels sold in the military PX for just fifty cents a pack, “Amis” (short for both American cigarettes and the American people) became the most popular form of contraband. Farmers accepted them for potatoes, eggs, and butter. Thirty cigarettes would get you a chicken, sixty a pound of butter.

As youngsters, we had developed our own version of tobacco money. After school we would comb roadside embankments for cigarette butts tossed out of jeeps and trucks by American soldiers. German smokers wouldn’t discard their butts, they’d recycle them into new cigarettes. In time, our buyers grew confident that the tobacco we had collected in our little matchboxes was 99.9 percent American.

By the fifties, cars shipped over by American soldiers were a common sight on the Autobahn. Because their size made them unwieldy on the narrow, winding streets of medieval German towns and small country villages, they were quickly dubbed "Straßenkreuzer", which literally translates to Street Cruiser but is closer to Land Yacht by the meaning intended.

The Americans took as much pride in their cars as the Germans did. In postwar America, some people would judge you by the car you owned, the "Joneses" thing. It made sense in a perverted way because you couldn’t lease a car unless you needed a fleet of them; you had to buy your car and put money down and pay off the rest in no more than thirty-six monthly installments. The point being that an unskilled laborer wouldn’t be tooling around in a brand new Chrysler Imperial without having won the lottery.

That went away for a while when cars began to all look alike on account of aerodynamics but now seems to be making a comeback. I have no idea why. In the fifties when you drove a Cadillac, people could see you were rich from a half-mile away. With today’s cars, I can’t tell a Ford from a Chevy until I’m close enough to touch bumpers and read the logo on the trunk lid.

In between the status symbols were the cars that showed the world you were different. The bullet nose ‘airplane’ Studebakers did that in spades. I saw my first Studebaker while stepping off the train in Stuttgart, a white 1950 Starlight Coupe sitting on a flatbed railcar on an adjoining track. I’m nearly as big a fan of airplanes as I am of automobiles. For me, you couldn’t have brought the two worlds together any closer.

Another make and model that belonged squarely into the ‘doing it my way’ category was the ’55 Ford Thunderbird, a car I first spotted in a suburb of Stuttgart while walking to work. Thunderbird Blue, which is really more like turquoise, with turquoise and white interior. I mean, c’mon, you gotta admit, American fifties cars had style!

As I’m writing this, both cars are sitting in my garage in upstate New York. Maybe I am a little different. I’m an introvert who writes software but doesn’t own a cell phone because I don’t feel the need to be that connected. And I hate texting. So what if people think I’m antediluvian. My friends know better. As for anyone else, I’m fortunate to have discovered early on that once your reputation is ruined you can live life quite freely.

My very first ride in an American car came while I was hitchhiking to a youth hostel in Hamburg in August of 1953. Two GI’s in uniform driving a yellow ’51 Ford convertible stopped to take me as far as Heidelberg. Top down, sun shining, radio loud enough to hear Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald and Glenn Miller in the backseat – God, it was heaven.

Hey Jerry, do you think maybe that memorable ride in the yellow Ford convertible tipped me to becoming a Ford man? You’ll meet Jerry in another chapter. He’s a close friend and a Chevy man. His cars range all the way from a 1921 Brewster Town Car with leather fenders to a 1955 Austin-Healey powered by a 350 Chevy engine – with a 1920 Model 48 Locomobile and a fifties Fairmont Railroad Speeder somewhere in the middle. Raising nary an eyebrow among his friends, there are no railroad tracks leading to or from his garage, and the Healey may be the only Chevy-powered vehicle in Jerry’s eclectic collection. Makes perfect sense when you factor in that he also hates to fly and so enlisted in the Air Force.

Jerry's Garage with red 1921 Brewster Town Car in the background

I can’t hold the Chevy thing against him, he’s always been a true car guy. Fact is, I too own a Chevrolet, a ’56 two-door 210 powered by a 480 hp 350 GM short block, the one with the distributor in the back where it’s hard to get to instead of in the front where it belongs, like in a Ford. Engels Gualdani, another friend who owns Great Lakes Classic Cars, built it for me from the ground up with the help of Bert and Jon.

There’s really no better choice for building a fifties car from scratch than a tri-five shoebox Chevy. There, Jerry, I said it.

My girlfriend Terry owns a ’65 Ford Thunderbird and used to own a 2008 Z51 Corvette and 2002 Special Edition Pontiac TransAm, all convertibles, so she’s either in the middle on this or a traitor to both marques, Ford and General Motors, depending on how you look at it.

My second ride in an American car was in a 1950 Chevrolet Deluxe Coupe when a GI gave me a lift from the roller skating rink to the movie theater at Patch Barracks, an American Army garrison near Stuttgart. I had joined the German-American Youth Club to meet American teenagers my age. Nearing the cinema, I wanted to compliment him on his car, but the best I could do using my high school English was “Nice car.” “Thanks,” he beamed, leaning back in his seat – “Powerglide.” Automatics transmissions were new on the options list that year. Told you the GI’s were proud of their automobiles.

Five years earlier, in the fall of 1945, we had brought a small handcart to the train station in Winterbach to collect my uncle Eugen. My uncle had been drafted into the German Wehrmacht at the outbreak of the war and spent several months in a Rheinwiesenlager, a group of 19 temporary American POW camps along the Rhein that held surrendered German soldiers from April 1945 to September. After Germany had capitulated, many of its soldiers deliberately sought out American captivity in the hope of better treatment. Within days, the U.S. occupation forces found themselves with between one-and-a-half and two million prisoners of war, a logistical nightmare for which they were unprepared.

To circumvent international stipulations of the Geneva Convention that dealt with the handling of prisoners of war, German soldiers who had surrendered were termed "Disarmed Enemy Forces" instead of being called prisoners of war, and internal administration of the camps, from cooks to doctors, was handed over to the prisoners. In the beginning, the camps, being provisional, contained no tents or sanitation. In April and early May 1945, the supply of food was at best irregular and nowhere near enough, after which it slowly improved. By June, food rations were finally deemed sufficient, after several thousand prisoners had died from malnutrition and disease. In the course of May and June, all the camps were given latrines, kitchens, and hospitals. By September 1945, most of the camps had been closed.

Before we pass judgment on the American occupation forces, some of the blame must rightfully go to the British who stopped accepting German prisoners after the Allies had crossed the Rhine at Remagen, putting immense strain on the Americans to somehow put up temporary camps for close to two million POWs who kept on coming; and to the French who demanded (and by treaty received) 740,000 able-bodied German POWs from the Rheinwiesen camps for forced labor on farms and in French coal mines; and finally, to a few unscrupulous German farmers near the camps who offered bread and apples to the prisoners in exchange for wedding rings and watches, which is how my uncle Eugen lost his. Food was scarce throughout Europe after the war, as were most things we consider essential to civilized living. Blame? One of the few things available in abundance.

Forced labor was codified in the protocol of the Yalta Conference in January 1945, where it was agreed to by Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Under pressure from the United States, French officials told the German POWs in 1947 that the last of them would be able to return home by the end of 1948. But there was a twist: Some German POWs, like the hundreds of thousands who worked in agriculture, had it better in France than they would have in war-ravaged Germany. French officials didn't want to completely relinquish the supply of cheap labor, so they offered the prisoners the chance to stay on in France — as French residents, with pay. Almost 137,000, many of them from the Russian zone of Germany, took them up on it.

Unfit for forced labor, my uncle avoided the transfer to France. He was released in 1945 and put on a train to Winterbach, the village down the hill with the church and the railroad station. Too weak to walk from starvation, he handily fit into the small handcart we normally used to carry supplies to our half-acre plot, and he was light enough so we could pull the cart up the hill. My mother was boiling potatoes in the kitchen that my uncle was ready to inhale "al dente" as soon as he spied them. A neighbor quickly stepped in and covered the pot, convincing him that his emaciated body couldn’t possibly digest them.

During the war, his wife Helene had lived with her two children in Kőnigsberg, a city in East Prussia, while her husband served in the military. Kőnigsberg was annexed by the Russians and is now known as Kaliningrad, making my aunt one of the many thousands of persons displaced by the war. She arrived at our doorstep months after her husband’s release, with their son Peter and daughter Brigitte and a tattered baby carriage filled with personal belongings. It had been an 800-mile trek and I remember to this day how blown away I was to see the wheels of the carriage worn down to bare metal, the tires shredded.

When my uncle Eugen was well enough to work, he and his family moved to Winterbach. He had been trained as a gardener for which there was next to no demand after the war, so he drove a truck cobbled together from bits and pieces of other trucks that in a million years couldn’t have been made whole again. Stuff happens to trucks in a war zone.

Eventually, my aunt and uncle decided to put all their furniture out on the lawn with price tags and start a new life in America. None of them spoke a word of English, not uncommon for immigrants, but within a year, Peter and Brigitte were fluent enough to switch from German to English whenever it was to their advantage to keep their parents from listening in on their conversations. All the while my uncle tried unsuccessfully to get people to spell his first name Eugen instead of Eugene, a reasonable request since Eugene is a girl’s name in Germany.

In the spring of 1956 news arrived from America. When my mother handed me the letter, I could tell from her eyes she’d been crying: My uncle had found someone who would sponsor me to come to America and, no less essential, a bank in Rochester that would loan me the money for the ticket if my uncle cosigned.

This was big, a life-altering event, and I knew right away how crushing the letter must have been when my mother first read it. I was the oldest, her firstborn. If I accepted my uncle’s offer, it would be the fulfillment of my wildest dream, the chance of a lifetime. For her, it would mean extra hours of fieldwork on top of the many late-night hours she already spent knitting socks for the village residents, on an ancient hand-powered knitting machine passed down to her by our grandmother.

She could easily have asked me to stay. I was still a teenager and would be unable to get a visa without her consent. But I already knew what she would say. We had both in our own way defied a war, standing together once I was old enough to offer support. This was going to be a decision I alone would have to make and then live with whatever came of it.

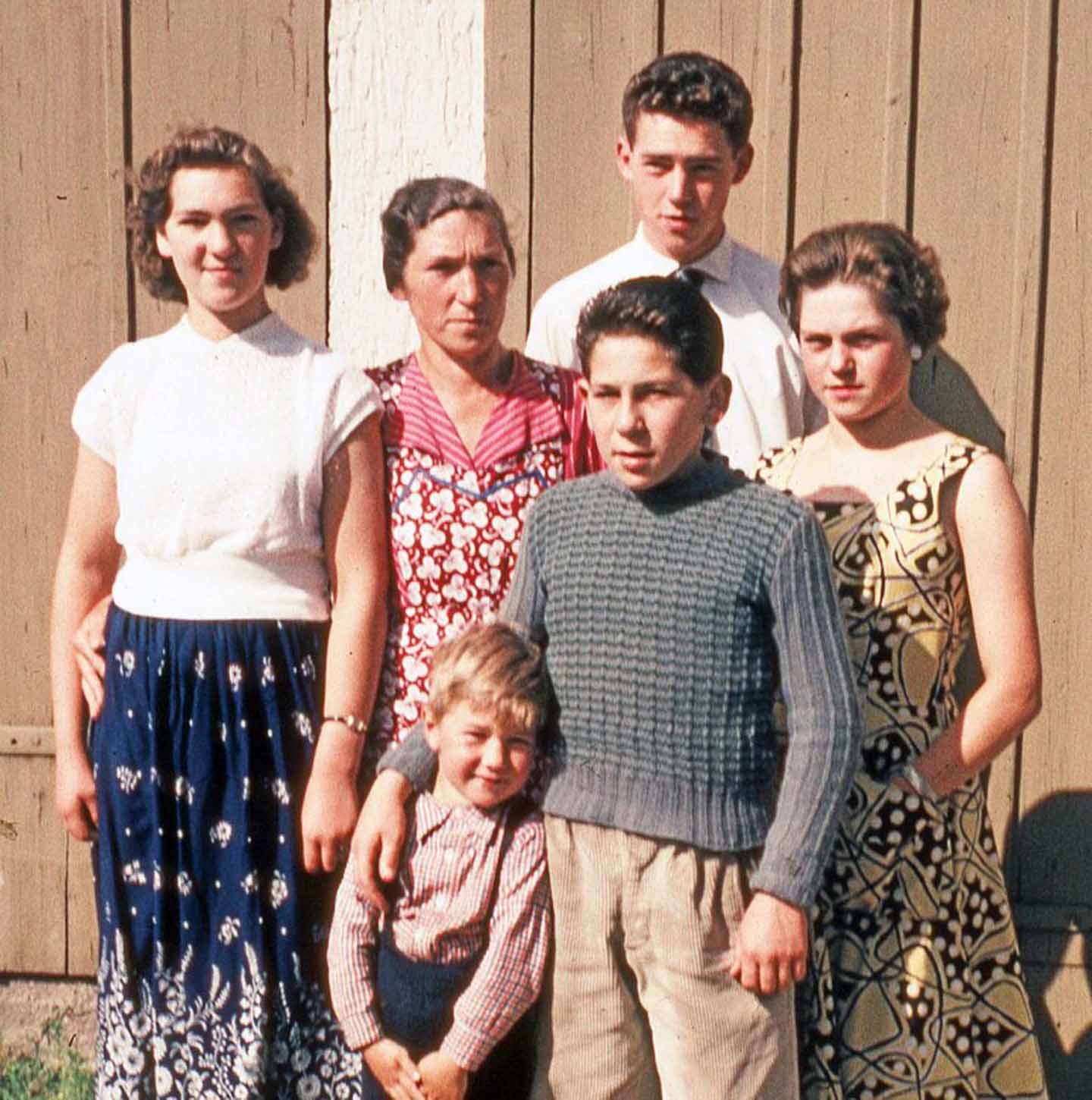

Photo on left - front row, left to right: Me, my cousin Peter Reiniger, my brother Eugen, my cousin Brigitte Reiniger, my sister Erika. Back row: My uncle Eugen Reiniger, his wife Helene, our mother with Werner, our aunt Anna Calbantner, my sister Erna, and Hedwig Sigle (our neighbor). Photo on right - Our mom with my youngest brother Werner and my younger brother Eugen.

Overshadowing it all was the prospect we might never see each other again. “We” meant my Mom, my two brothers and two sisters, their yet to be born children and grandchildren, and my uncles and aunts and friends and classmates – everyone I had gotten to know and with whom, in one form or another, I had shared some part of my life while growing up in Germany.

Farewell party at the Gasthaus Krone in Rohrbronn.

Photo on left, left to right: Karl Hasert, Karl Müller, Oskar Zeyer, (unknown - I'm sorry), Fritz Waibel, me, Karl Vester.

Photo on right, far right: Walter Schurr.

For four years my consistent travel companions (and best friends) on the same train to and from Stuttgart, where all four of us were business apprentices.

From left to right: Waltraud Ziegler, Reiner Ortmann, and Ella Schwegler. Miss you guys!

Historically, few immigrants ever revisited their country of origin. My mother’s brother Karl had gone to America in the twenties, never to return. Even telephoning had to be prearranged and cost nearly a dollar a minute. No private phones existed in the village. The one bright side was that I could assist her financially with money earned in America, the way many immigrants do to this day.

From left to right: My sister Erika's daughter Gerda, and Gerda's daughters Mareike and Janina.

A visa to enter the United States as a legal resident was granted in May of 1956 by the American Consulate in Munich. My uncle had originally booked a passage for me on the Italian liner Andrea Doria that was scheduled to arrive in New York on July 26, then changed it to a KLM flight arriving on July 7. Crossing the Atlantic by air was more expensive but would put me into Rochester three weeks ahead of the Andrea Doria and my uncle was in the midst of an upstairs remodel of their house on 14 Wooden Street for which he said he could use my help.

I arrived in America with $25.00 in my pocket. That’s all my mother and I could scrape together. I owed Lincoln Rochester Trust Company in Rochester $343.88 for the airline ticket. The helicopter ride was free: KLM had me flying into one airport (Idlewild, later renamed JFK), and out of another (Newark) for the connecting flight to Rochester. It was all on the same ticket so they had to shuttle me between the two airports at their expense. My first flight ever on an airplane and a helicopter. What a country!

Sadly, the Andrea Doria never arrived in New York that July. The ship sank off Nantucket Island on the 27th, having been rammed in dense fog by the MS Stockholm. Although 1,660 passengers and crew survived, 46 perished as a result of the collision.

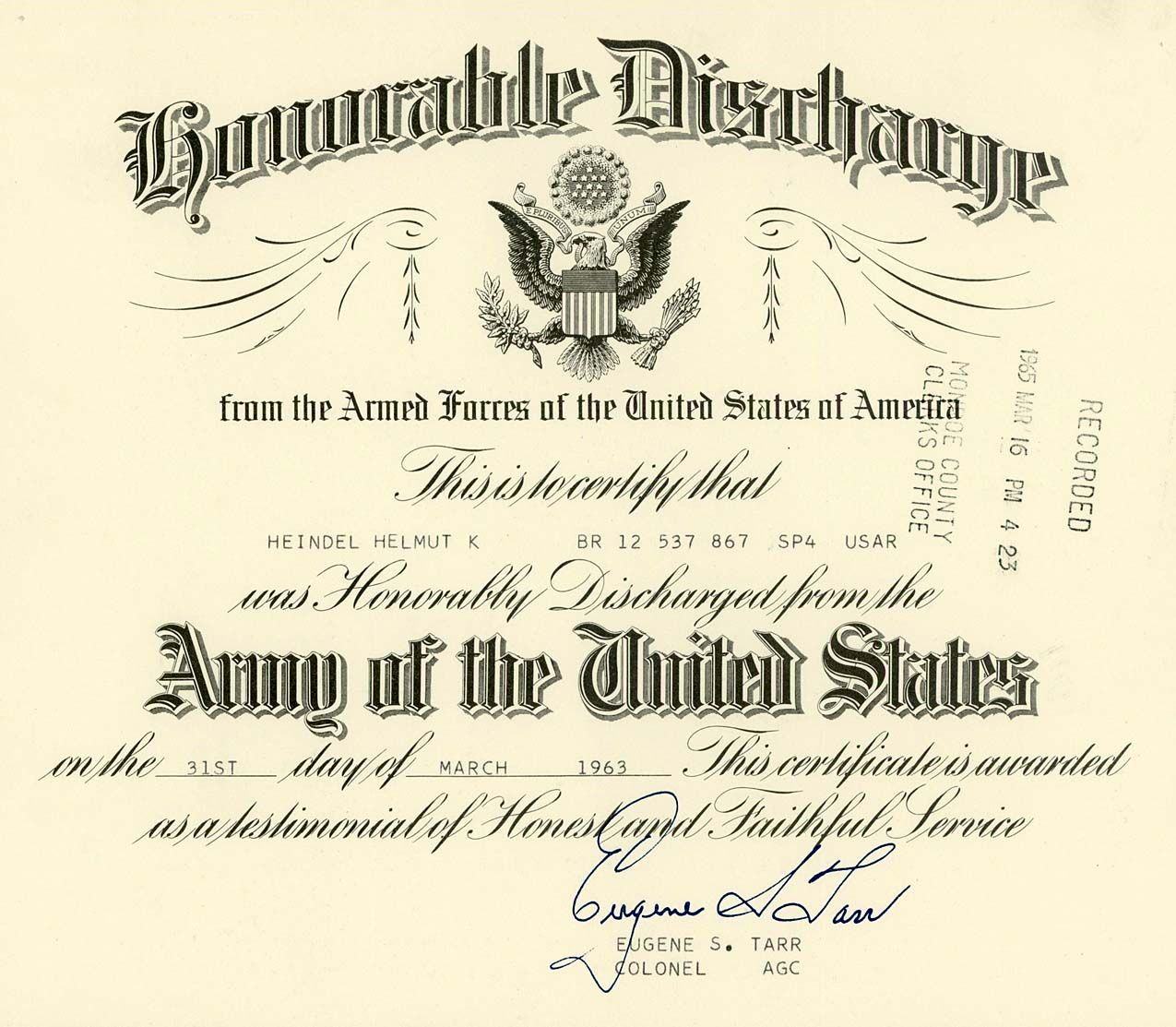

I became a citizen of the United States on November 20, 1962, after the mandatory waiting period. My tipping point to become an ‘American’ by ideology had been reached seventeen years earlier, at age nine, somewhere between the night of the horses and the CARE packages and the black sergeant extending his hand, holding out an orange and a stick of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum.

Left to right: Helmut Schurr (my mother's neighbor), my sister Erika, her husband Erhardt, my youngest brother Werner (behind Erhardt) my sister Erna, her husband Richard (an American soldier stationed in Germany).

It would be nine years before I could fly back to Germany. My service in the Army, my marriage, the birth of our son Raymond, and trying to carve out a career, made it difficult to get away in the 1950s. Not to mention paying the high airfare of more than $600 per person, both ways, which in today’s money would equal $5,754.

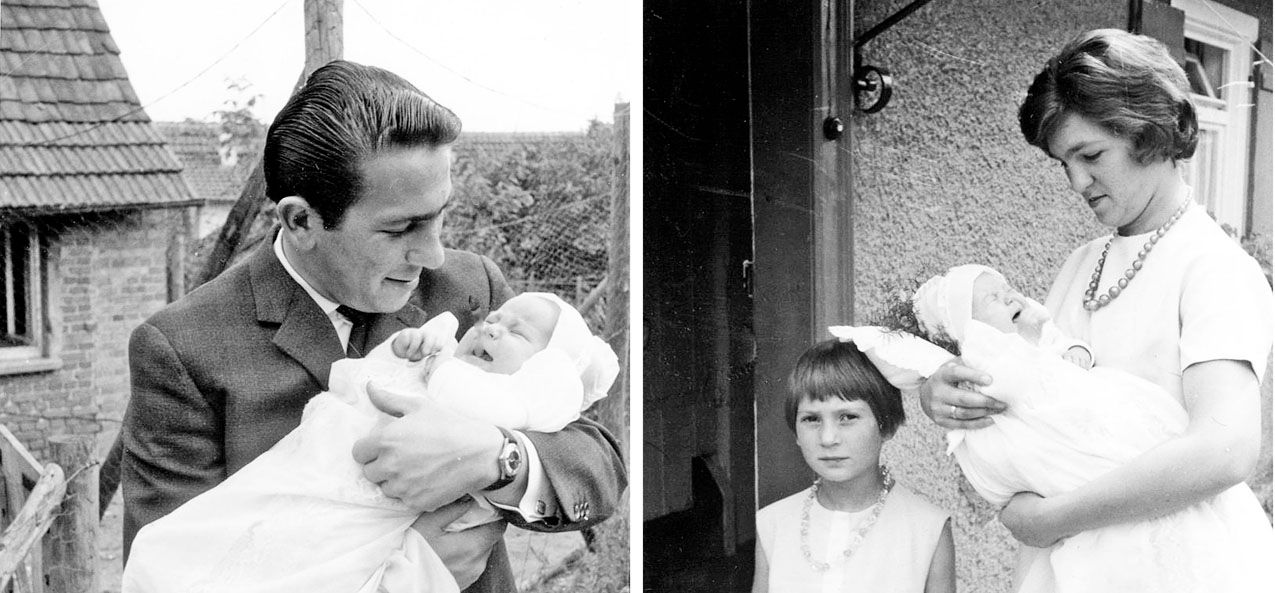

My brother Eugen and my sister Erika at the christening of Erika's daughter Marion.

In April of 1965, I was asked by our French office manager to assist them at a trade fair in Paris. Bausch & Lomb, my employer, was the first company in the world to offer a commercial laser to the scientific community. I was to demonstrate the laser to the show’s visitors. That worked well, if only for a day.

The demos could have lasted longer had the film Goldfinger not opened in Paris theaters at the same time. Also if some visitors had not expressed concern about being cut in half by the laser, (as James Bond almost was in the movie), and then relayed those concerns to the Sûreté, the criminal investigation department of the French government. The result was that for the rest of the show, we were told to display the laser in static mode only. Paul Belilovsky, the office manager, and I both thanked the gendarmes for their understanding. The small laser had next to no power and couldn’t have hurt a fly.

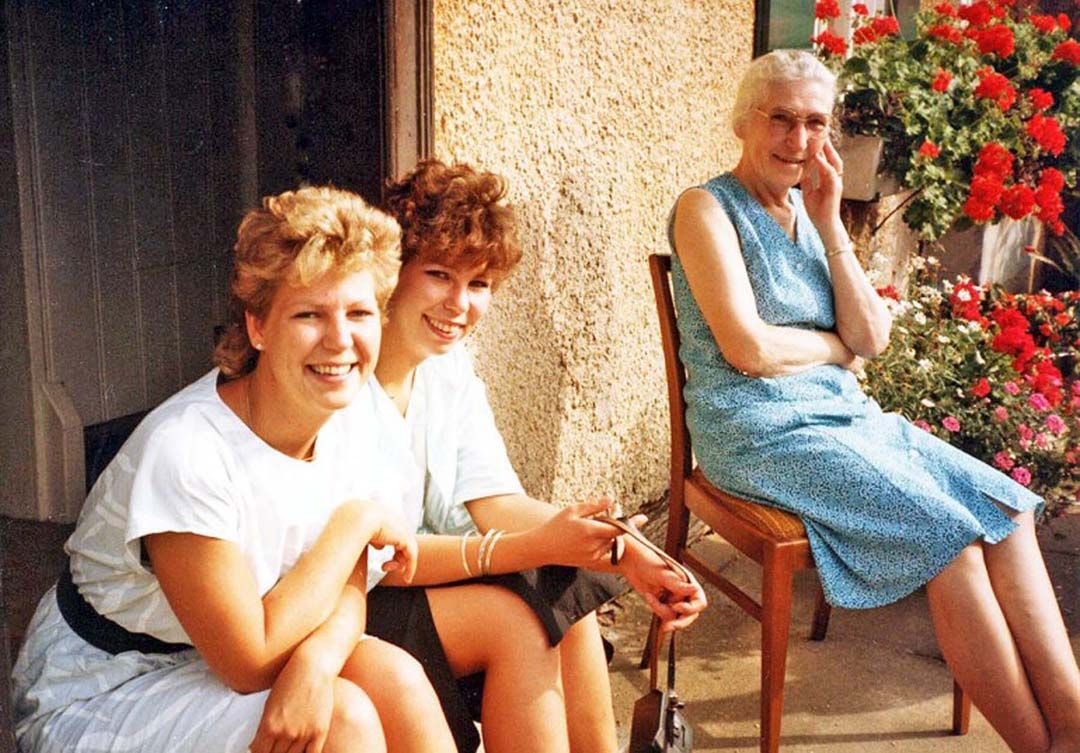

From left to right: My sister Erika's daughters Marion and Gerda, and my mother in front of her house in Rohrbronn, Germany.

Traveling by train from Paris to Winterbach after the show closed took but a few hours. My mother and brothers and sisters and I had talked on the phone from time to time, and always at Christmas. But seeing them in person again was wonderful. I had vacation time coming so I stayed in the house I was born in for nearly two weeks. A lot of catching up to do, and so much had changed. A few cows were still around, but Germany’s unexpectedly quick postwar recovery had paid for underground sewers and flushing toilets which for me was sort of a big deal.

The new, modern Rohrbronn. In the valley below, you can see the village of Winterbach.

Many residents of Rohrbronn now had cars that allowed them to commute to Stuttgart, home of the Porsche and Mercedes-Benz auto plants. The village was beginning to become a rich people’s suburb, with swimming pools and all the trimmings. During the next thirty years, my visits would become more regular, first with Effie, my spouse, then with Terry after Effie had passed away. My sister Erna got married to Richard, an American soldier stationed in Germany, and they both moved to Tacoma, Washington when Richard was discharged. My sister Erika and my brother Eugen also married and both moved to Plȕderhausen, a town not far from Rohrbronn. I sponsored my youngest brother Werner so he could come to the States as a legal resident. He joined the Army, became a citizen, and then served in Korea.

One thing that hadn't changed: The "Schneckabuckl" was as steep a hill to climb as ever. Before or after a glass of Most (Hard Apple Cider).

Photo on the left: It wouldn't surprise me if nearly every one of my relatives living in Germany had put more miles on the fender of Richard's 1952 Cadillac than Richard had put on the car as a whole while he was stationed in Germany with the American Occupation Force. That's our mother taking her turn when Richard and Erna drove up to Rohrbronn for a home-cooked meal. Note the USA Licence Plate. Photo on the right: Celebrating Christmas in Plȕderhausen, Germany with my brother Eugen, Terry, and Eugen's wife Elisabeth.

Once air travel became more affordable, our mother decided she too wanted to see America. She visited both me and Erna on separate occasions and stayed with my sister twice, for several months. Turns out she loved America and flying and was particularly fond of takeoffs. Way to go, Ma!

Photo on the left, seated: Uncle Eugen, our mom, aunt Helene. Standing behind them: My cousin Brigitte (Eugen and Helene's daughter) and her husband Gene.

Photo on the right: Uncle Eugen introducing his sister to the novelty of motorized lawn mowing.

I say novelty because lawnmowers don't exist in most civilized countries, owing to there being no lawns to speak of in such countries. You know, that lush green stuff in your yard you're so proud of but that often gets in the way of what otherwise could have been a nice afternoon nap? It gets in the way because you over-fertilized what is intrinsically a field of weeds!

You did this because you wanted your field of weeds to look nicer than your neighbor's field of weeds, the Joneses' kind of thing. You probably knew full well that grass is a weed but you don't friggin' care. At least you're getting some exercise. That may have been true before lawnmowers became the riding type with noisy unmuffled motors, and a padded seat to alleviate numb-butt. Sort of kills your whole argument, doesn't it, in much the same way golf carts killed the touted health benefits of an 18-hole five-mile walk.

Golf carts were only beginning to gain popularity in 1956, the year I left Rohrbronn to come to America. I don't play golf but will readily admit that, because carts are now available everywhere, it's the one sport you can plan to play the rest of your life.

So why are there virtually no lawns that need cutting in Germany? Because as late as 2007, the food-self-sufficiency rate of the country was just 80%. Every square yard of arable land is used to grow edibles — for man or beast — to this day. As you would expect, postwar conditions were much worse.

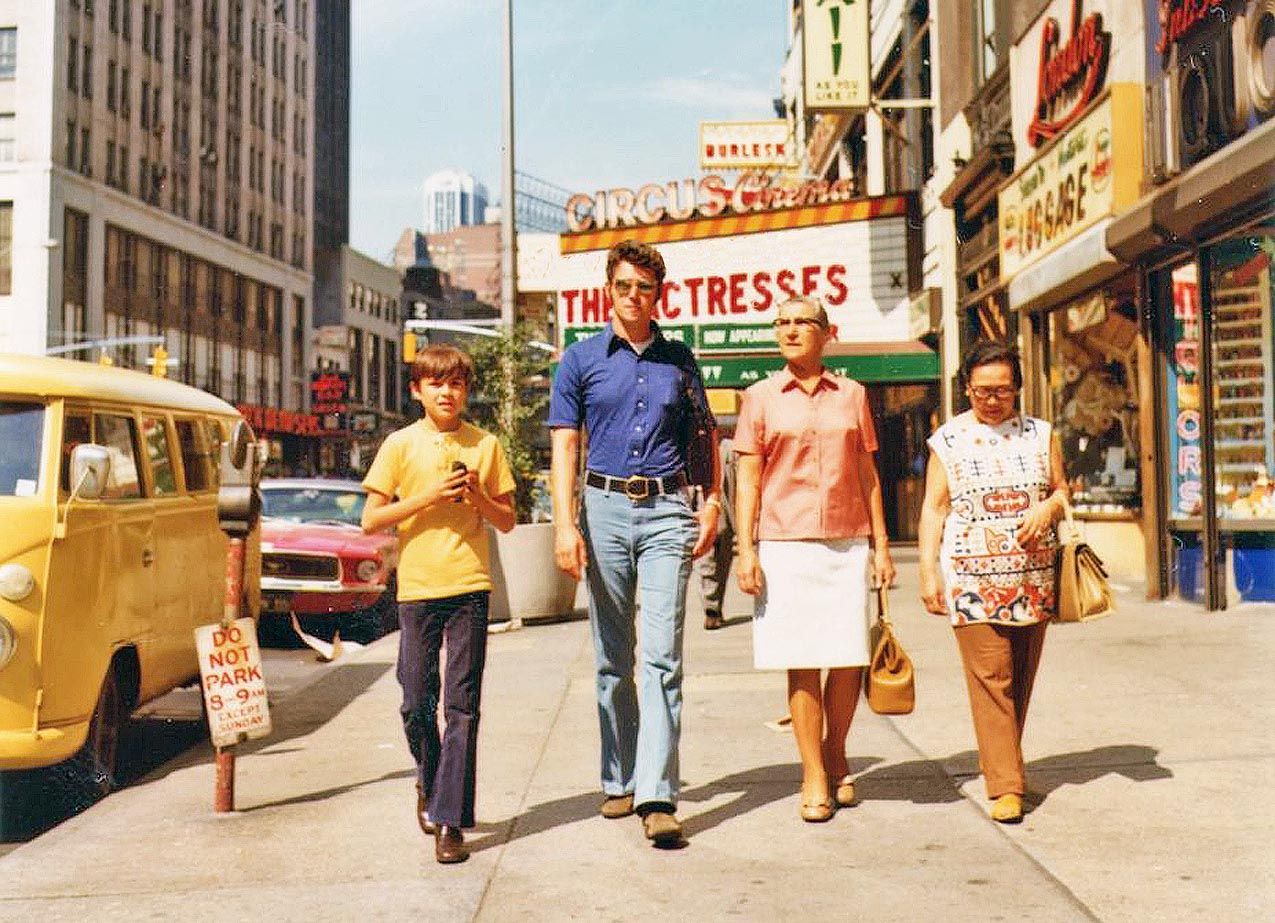

Photo on the left: Mom boarding "That's Her", Chalk's water taxi based in Fishers Landing, on the way to the Vogt's cottage on Grenell Island.

Photo on the right: My son Raymond, me, our mother, and Effie's mother, strolling down 42nd Street in New York City.

Before long, all my siblings and nieces had come to visit us in Rochester, especially after Terry and I had bought, torn down, and rebuilt from scratch a Summer House on Lake Ontario. My niece Gerda was first to arrive (before the lake house was inhabitable), followed by Eugen and Elisabeth, then by my niece Marion with her husband Otto and their two daughters, Miriam and Melanie. On their second visit, Marion brought along her mom (my sister Erika).

We found the old wooden entrance sign buried in the sand under the house we demolished. It was originally used by the Seabreeze Amusement Park, back in the early 1920s, and might have been thrown in the trash because its design had become "dated".

From left to right: My great nieces Miriam and Melanie, and my grandson Karl on the beach in front of our house at Seabreeze.

That’s as high as I’m willing to climb up the family tree before we reach heights that can make a person feel dizzy. I’m not shy about telling you that I'm not deep into family affairs, nor am I excessively gifted that way. I forever need help from Terry about who to call a niece and who to call a cousin. Not that I would ever lose sleep over it (except for right now while I’m writing this, to keep me from looking illiterate). I'm fond of my extended family, love 'em all, in America and in Germany, all the same.

Here is where a professional editor, had I hired one, would jump in and tell me that the last few pages of this chapter read like a family album, which I grant you is true but it's my book and my family and I'm not leaving anyone out. Not intentionally. Let's be honest here, would you be that brazen if you were me and had to answer for the inexcusable omission at your next family get-together? With the person you overlooked now present in the room, but for now and forever not in the book? Your book! In which, by the way, everybody in the whole world seems to have been mentioned? I didn't think so!

From left to right: My brother Eugen and his wife Elisabeth, my sister Erna and I on a sightseeing cruise in the Thousand Islands on a hot summer's day.

From left to right: I, my niece Marion's husband Otto, my sister Erika, and her husband Ehrhardt.

Our mother and my sister Erna at Disney World in Orlando, Florida.

In November of 1996, our selfless and courageous mother departed an often harsh, demanding life on earth after a short illness. Terry and I had already scheduled a trip to Germany to see her one last time. Then my brother called to say “you need to come now.” Three days later I was at her bedside. It was the last time I would hold our mother’s hand.

The guilt of having deserted her and my brothers and sisters diminished over time. It would never melt away into the unaware. In my final phone call I thanked her for not trying to talk me out of leaving them in Rohrbronn. “Oh, it’s alright, Helmut, let it go,” she answered. Then she asked: “But were you happy?” Sensing that this would be the last time I would hear her voice, I had a hard time keeping it together. But, I had made the call from the office phone during working hours and the shop was still open for customers.

Hours later, having pried open a door to a forbidding and rarely visited soul attic filled with deeply hidden memories, I lost it. “Damn’ you, Ma’,” I cursed out loud in the now deserted print shop. “What in God’s name made you give up the best years of your life so all of us could find happiness in ours?”

A family portrait taken the afternoon of my departure for America.

My eyes welled up to where I could no longer hold back my emotions. What should have been grief was exploding as anger. I wasn’t berating our mother. I felt rage at a world plagued by indifference, heightened by disdain for a civilization so eager to surrender to its dark angels. In Germany, my generation is known as the "Kriegskinder," the war children. On that day, in an empty New York print shop, the war had revealed its toll.

“In love we find out who we want to be. In war we find out who we are.” Kristin Hannah in The Nightingale.

By the time Terry and I arrived two weeks later on our originally scheduled visit, our strong, kindhearted, and fiercely independent mother had passed away.

Terry, as you may have read, was born in Rochester, New York. I emigrated from Germany in 1956. It would be ludicrous to think that any family left behind 65 years ago would still be the same six decades later. Some of your relatives will have gotten married, some will have born children and grandchildren. And some, sadly, will have died.

This might be a good time to express how relieved and thankful I am that all the babies, toddlers, mothers, and fathers in the next four photos are alive and well. The same goes for my son Raymond and his wife Christine, and my grandson Karl, pictured elsewhere, who live miles away in California.

Terry and I consider ourselves blessed as well to have come this far, still in excellent health, having survived the Covic-19 Pandemic. This we credit in large part to following the advice of doctors and scientists instead of buying into the manure spread by Fox News and callous politicians. Not only is masking and social distancing and getting vaccinated the right thing to do in this kind of war, it’s also the responsible thing to do for the well-being of our neighbors. Especially when there is no end in sight and the virus keeps sprouting variants and killing millions.

The difference between genius and stupidity is that genius has limits!

But here’s another wrinkle Terry and I had to consider: Even if our political affiliations had us question the proven benefits of masking and distancing and vaccinations, with the multitude of doctors and scientists in our family, what choice did we have? On what planet would we have won that argument? “Pick your battles," we are told. Times are challenging enough as is.

Upper left: My great niece Melanie and her new baby Jaron.

Upper right: Melanie, Jaron and Johannes - Doctor of Internal Medicine.

Lower left: Miriam, a Doctor of Gynecology, and Tristan, a researcher with a PhD, with their daughter Helena. It was rumored that the Doctor field Helena will choose for herself still hangs in the air.

Lower right: Jonathan, son of Miriam and Tristan and already a seasoned traveler, having flown from Germany to America before celebrating his first birthday so he could visit us at our beach house.

Copyright 2022 - Helmut Heindel